Dewey Loeffel Killed Nassau Lake, Countless Wildlife and Most Likely Some People.

When Private Property Becomes A Public Problem.

I wrote this a few years ago, after my friend EB and I went on one of our little explorations. I’ve updated it. This week demonstrated to me just how important this story remains and how crucial it is to protect the environment. It also illustrates how a single person’s financial gain becomes a community issue. While the toxins maybe different than those used on grapes, they are damaging all the same. Everyone deserves to know if their neighbors are using substances that have the potential to cause harm.

Nassau Lake, in upstate New York’s Rensselaer County, was once described by a local newspaper as “Little Lake George”—a charming designation suggesting weekend picnics, fishing rods, the wholesome recreations of mid-century American life. That was before Dewey Loeffel, who operated a waste oil removal business from 1952 to 1968 on nineteen acres of low-lying land between two wooded hills. For over sixteen years, his unlined landfill swallowed more than 46,000 tons of industrial hazardous waste: solvents, waste oils, polychlorinated biphenyls, acids, sludges, and sundry other poisons. General Electric alone contributed approximately 37,530 tons. Bendix Corporation and Schenectady Chemicals rounded out the guest list at this toxic dinner party.

The waste was dumped into lagoons, poured into pits, buried in drums. Some of it was simply pumped onto the ground. Some of it was burned. By 1970, Loeffel himself acknowledged that the swamp he had transformed into a dumping ground was devoid of plant and animal life. One pictures him surveying this moonscape of his own creation with the satisfied air of a job well done.

The neighbors noticed. They noticed the dead fish floating in the streams. They noticed their cattle dying. They noticed the fires that erupted spontaneously at the dump, as if the earth itself were registering its objection. In 1968, the State of New York finally ordered Loeffel to cease operations. He obligingly covered the mess with soil, constructed some drainage channels, and presumably went about his business. But by then, the toxins had embarked on their own journey—seeping through aquifers, trickling into tributaries, making their leisurely way toward Nassau Lake and far beyond.

To understand the scope of what Dewey Loeffel’s dump unleashed, one must trace the path of water as it flows downhill from that nineteen-acre parcel of poisoned earth. The contamination did not politely confine itself to the property lines. It migrated, as water does, following the ancient logic of gravity and watershed.

First came the Northwest Drainage Ditch, the primary channel carrying surface runoff from the landfill. This fed into a low-lying area and then into what was bureaucratically designated as Tributary T11A—a 1,900-foot stream that the residents of Nassau eventually rechristened Little Thunder Brook, naming it after a figure from the Anti-Rent Wars of the 1840s. The renaming was an act of reclamation, an assertion that this poisoned waterway belonged to the community and its history rather than to the EPA’s filing system. The sediment along Little Thunder Brook’s banks tested at PCB levels exceeding 1,000 parts per million—concentrations so high that the EPA ordered emergency removal in 2018.

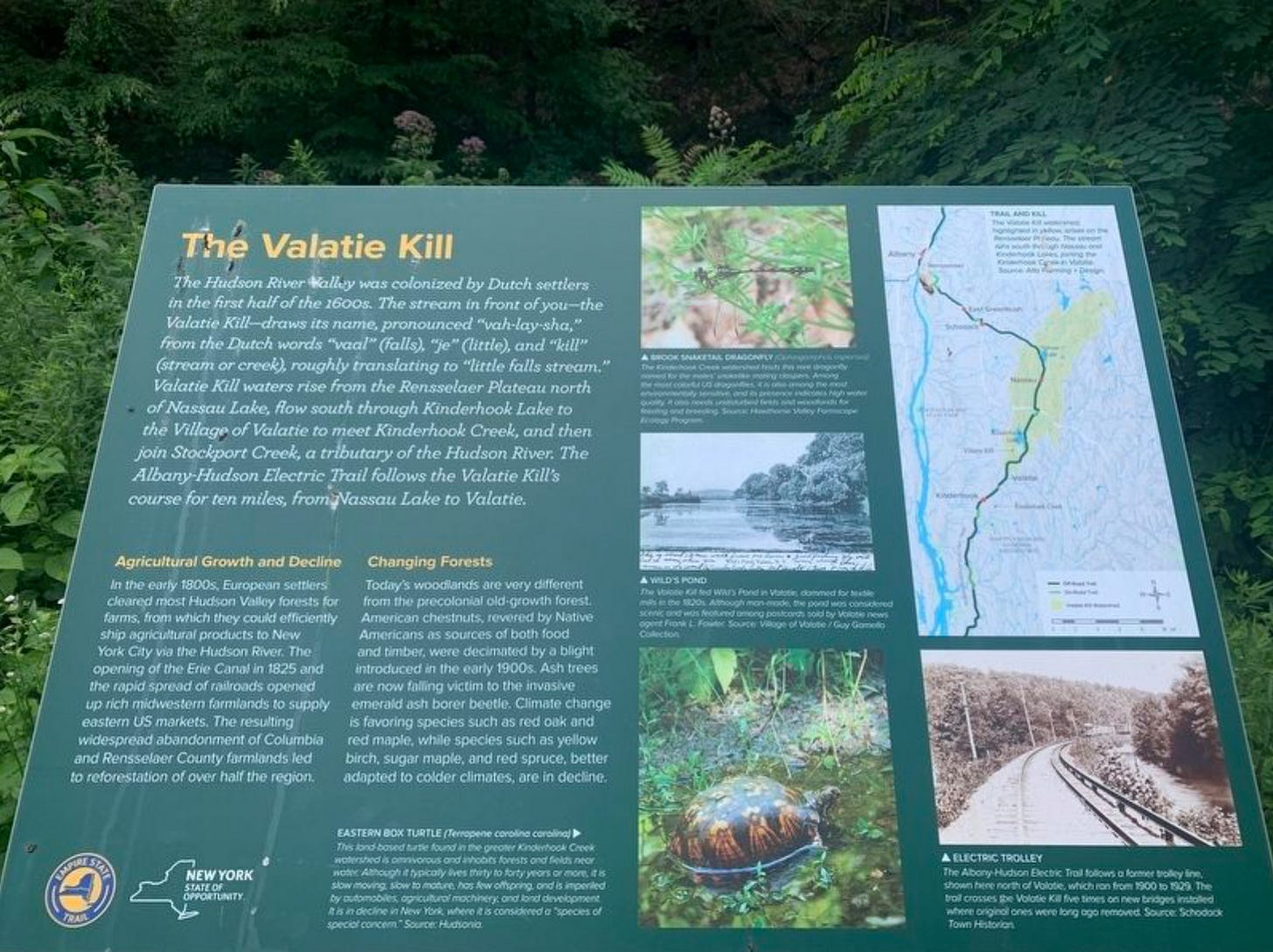

Little Thunder Brook empties into the Valatie Kill, a protected trout stream that once supported a thriving fishery. The Valatie Kill flows southwest for approximately 2.7 miles before reaching Nassau Lake. But Nassau Lake is not the terminus. The contamination continues downstream into Kinderhook Lake in Columbia County, then into Kinderhook Creek, then Stockport Creek, and finally—inevitably—into the Hudson River, the nation’s largest Superfund site, where General Electric’s PCBs have been accumulating since the company began dumping them directly into the water decades ago.

The water treatment plant that GE and SI Group constructed at the landfill site extracts contaminated groundwater, treats it to EPA-acceptable levels, and then discharges it into the Valatie Kill. This is the solution: take the poison, dilute it sufficiently to meet regulatory thresholds, and release it into the same watershed it has been contaminating for seventy years. The villages and towns downstream—Valatie, Kinderhook, Stockport—have watched this treated effluent flow past their communities for more than a decade now, trusting that the EPA’s acceptable levels are, in fact, acceptable.

In 2021, torrential rains tested that trust. Up to five inches fell on the area, causing widespread flooding. Mead Road, where the landfill sits, was shut down. Sediments from the Superfund site poured into Little Thunder Brook and down into the Valatie Kill. “Because of the volume of transfer down the streams, this isn’t just a Nassau problem,” Town Supervisor David Fleming observed. “This is a Capital Region problem.” The EPA acknowledged that the storm “may have transported PCB-impacted sediments to downstream areas”—a rather delicate way of describing toxic sludge washing through a protected trout stream and into the lakes and rivers that thousands of people depend upon.

Meanwhile, there is also the Southeast Drainage System: surface water flowing from the Loeffel site into an unnamed tributary that feeds Valley Stream, which flows through Smith Pond before discharging into Nassau Lake. State investigations determined this pathway was “not significantly impacted”—cold comfort to anyone familiar with how such assessments tend to underestimate long-term cumulative effects.

Then there are the groundwater contamination plumes, spreading invisibly beneath the surface. PCB contamination persists for at least half a mile south of the Superfund site, with five known residential well contaminations. In 2023, the EPA detected elevated volatile organic compound levels at 320 feet below ground level—the poison having migrated not just horizontally through the watershed but vertically, deep into the aquifer that supplies drinking water to homes throughout the region.

The official tally of affected waterways reads like a geographical indictment: the Northwest Drainage Ditch, the Low-Lying Area, Mead Road Pond, the Mead Road Pond Spoil Banks, Tributary T11A (Little Thunder Brook), the Valatie Kill, Smith Pond, Valley Stream, Nassau Lake, Kinderhook Lake, Kinderhook Creek, Stockport Creek, and ultimately the Hudson River. New York State maintains fish consumption advisories for Nassau Lake, the Valatie Kill, and Kinderhook Lake. Women under fifty and children under fifteen are warned to eat no fish whatsoever from these waters. Everyone else is advised to limit consumption according to species and location—as if anyone could reasonably be expected to calibrate their fishing habits to a matrix of PCB concentrations.

The Columbia County village of Valatie, population 1,800, lies just thirteen miles downstream from the Loeffel site. This winter, elevated levels of PFOS—a different class of toxic chemical—were discovered in the village’s public drinking water system. Whether this contamination originated at the Loeffel site remains uninvestigated. The state has given no indication it intends to find out. The village is working on treatment, filtration, mitigation. The source remains a mystery no one in authority seems eager to solve.

PCBs are, in the lexicon of environmental science, “persistent.” This is a polite way of saying they never go away. They do not biodegrade. They accumulate in fatty tissue and travel up the food chain with the patience of geological time. They have been linked to cancer, immune suppression, reproductive failure, and developmental delays in children. As David Carpenter of the University at Albany has observed, there is no level of PCB exposure that science can confidently declare safe. The chemicals may eventually disappear, he notes, but not in any human lifetime—perhaps over thousands of years. Small comfort to the residents of Nassau, who were not consulted about whether they wished to participate in this multigenerational experiment.

In 1980, New York State issued a fish consumption advisory for Nassau Lake. That advisory remains in effect today. Let that sink in: for forty-five years, the people who live near this once-charming lake have been warned not to eat what comes out of it. The “Little Lake George” has become a place where the catch of the day comes with a government health warning.

Here is where the story acquires its particular American piquancy. In 1980, General Electric—that beacon of industrial civilization, that bringer of good things to life—entered into an agreement with New York State covering the Loeffel landfill and six other PCB-contaminated sites. GE contributed thirty million dollars to a cleanup fund, and in exchange, the state agreed the company would never have to pay another dime. Ever. This arrangement, known as the “Seven Sites” agreement, must have occasioned considerable satisfaction in GE’s legal department. Thirty million dollars to make an open-ended liability disappear forever was, by any measure, a bargain.

Part of that money paid for a clay cap placed over the dump in 1984. The cap was, one supposes, intended to contain the problem—to draw a line under the whole unfortunate business and allow everyone to move on. The chemicals, however, had not read the agreement. They continued to migrate. They continued to poison. In 2009, when the EPA finally got around to collecting sediment samples from the waterways downstream, PCBs were still present, still spreading, still doing what PCBs do.

In March 2011, the Dewey Loeffel Landfill was added to the EPA’s National Priorities List—the federal government’s roster of the most contaminated places in America. The site, it turned out, contained twice the toxic load of Love Canal, that ur-text of American environmental disaster. One might think this distinction would have prompted urgent action, a marshaling of resources commensurate with the scale of the catastrophe. One would be touchingly naive.

What followed instead was the familiar Superfund minuet: studies commissioned, agreements negotiated, treatment plants constructed, all moving with the stately deliberation of continental drift. In 2012, GE and SI Group agreed to build a water treatment facility and pay up to ten million dollars. GE noted, with evident pride, that it had already spent more than twenty million on cleanup over the preceding decades. The company also pointed out, rather defensively, that it had never owned or operated the Loeffel landfill. This is technically true and entirely beside the point. GE did not need to own the landfill; it merely needed to fill it with poison.

The discoveries kept coming, each one a fresh reminder of just how thoroughly the area had been contaminated. In 2014, investigators found 1,4-dioxane—a known carcinogen—in treated water samples. In 2017, the EPA reached an agreement with GE to address the PCB-contaminated soil and sediment in Little Thunder Brook and several upstream waterbodies. In 2018, crews began excavating a “hot spot” where PCB levels exceeded 1,000 parts per million. In 2019, acting on a tip, EPA investigators found a 10,000-gallon chemical tank buried on the Loeffel family’s own property, along with leaking barrels and unsafe PCB levels in the groundwater. It seems Dewey Loeffel had not confined his environmental contributions to the landfill that bore his name. The old country saying about not fouling one’s own nest apparently held no purchase with him.

In 2020, after identifying more extensive contamination in Little Thunder Brook than previously understood, the EPA and GE reached yet another agreement—this one requiring a full remedial investigation to determine the extent of contamination and study feasible cleanup options. Stone dams were installed in the brook to limit sediment transport downstream while the investigation proceeded. One pictures these dams as a kind of environmental triage, an admission that the poison was still moving and that stopping it entirely was beyond anyone’s current capability.

And what of the people who have lived amid this slow-motion poisoning? In 1999, the town of Nassau and a citizens’ group conducted their own health survey of residents living closest to the site. The results were stunning: of one hundred respondents, seventy-six reported having some form of cancer. Neighbors had the same cancers. Pets had the same cancers as their owners. The survey revealed what epidemiologists call “clusters”—patterns that cry out for investigation.

No investigation came. Town Supervisor David Fleming has spent years trying to get state or federal agencies to conduct a comprehensive health study. The agencies have declined, citing various excuses. The largest public health question raised by the Dewey Loeffel site—what has this contamination done to the people who live near it?—remains officially unanswered. One suspects this is not an accident. The answer might prove inconvenient.

Meanwhile, the EPA estimates that a full risk assessment will not be available until 2026—nearly seventy-five years after the dumping began. The treatment plant continues to operate. The fish advisories remain in place. Property values in affected areas have cratered, leaving residents trapped in homes they cannot sell, drinking water from wells they cannot entirely trust, living atop a toxic legacy they did not create and cannot escape.

Town Supervisor Fleming has noted that when you look at the whole site at Loeffel, you are not talking about fifteen acres around the landfill. You are talking about impacts through the water table, tributaries, and soil contamination spanning more than a thousand acres. It affects more than just Nassau. It affects Kinderhook and Valatie and Stockport and every community downstream, all the way to the Hudson River.

Fifty-three million Americans live within three miles of a Superfund site. They are, for the most part, not the Americans who summer in the Hamptons or winter in Palm Beach. They are not the Americans whose concerns animate the editorial pages of prestige newspapers or the fundraising appeals of either political party. They are simply people who had the misfortune to live in places that powerful corporations found convenient for disposing of their waste—people who learned, too late, that the free market’s efficiency in externalizing costs meant their children would swim in poisoned lakes and their tap water would require filtration systems.

The Superfund program operates on the principle that polluters should pay. It is a noble principle, and it is largely fiction. The polluters pay for treatment plants and clay caps and endless rounds of studies. They pay lawyers to negotiate agreements that limit their liability. They do not pay for the cancers, the stillbirths, the children with developmental delays, the decades of anxiety, the loss of a way of life. Those costs are absorbed by the people of places like Nassau—communities too small and too poor to command the attention of anyone with the power to help them, left to drink their water and eat their fish and hope for the best while the cleanup crawls forward at a pace calibrated to corporate convenience rather than human need.

General Electric’s former chairman Jack Welch was once celebrated as the greatest CEO of his era, a titan of shareholder value creation. Somewhere in that glittering legacy of acquisitions and divestitures and quarterly earnings beats, there is a nineteen-acre landfill in upstate New York that will be leaching poison into the groundwater long after everyone who remembers Welch’s name has turned to dust. The Dewey Loeffel site is not part of the official GE story—not mentioned in the hagiographies, not celebrated at the business schools. But it is as much a part of the company’s legacy as any aircraft engine or medical imaging device. The chemicals do not care about corporate reputation. They simply persist.

And they travel. From a swamp in Nassau to Little Thunder Brook to the Valatie Kill to Nassau Lake to Kinderhook Lake to Kinderhook Creek to Stockport Creek to the Hudson River—an unbroken chain of contamination stretching across two counties, through protected trout streams and public water supplies, past villages where children play and fishermen cast their lines, all the way to the great river that Henry Hudson sailed four centuries ago in search of a passage to the riches of the East. He found instead a valley of extraordinary beauty, a landscape that would become home to millions. What he could not have imagined was that the descendants of those settlers would turn portions of that valley into a dumping ground for industrial poison, and that the poison would still be flowing, still be spreading, still be accumulating in the bodies of fish and birds and people, seventy years after the last truck unloaded its cargo at Dewey Loeffel’s landfill.

This is what a Superfund site looks like: not a dramatic explosion but a quiet, relentless seepage; not a moment of crisis but a permanent condition; not a problem to be solved but a wound to be managed, indefinitely, by people who had no hand in creating it and no power to make it stop. The people of Nassau have been living with Dewey Loeffel’s legacy for seven decades. They will be living with it for decades more. Somewhere, in a boardroom or a law office or a governmental hearing room, someone is undoubtedly describing this as progress.

And here is perhaps the most staggering detail of all, the fact that should keep regulators and legislators awake at night: this entire catastrophe—the poisoned lakes, the contaminated trout streams, the cancer clusters, the fish advisories spanning forty-five years, the plume of carcinogens reaching 320 feet into the earth, the chain of toxins flowing inexorably toward the Hudson River—all of it traces back to one man, operating on his own private property, answerable to no one.

Dewey Loeffel was not a corporation. He was not a government agency. He was a single individual who saw a business opportunity in accepting other people’s waste, who dug some holes in a swamp he owned, and who spent sixteen years filling those holes with 46,000 tons of industrial poison. No environmental impact statement. No public hearing. No regulatory oversight worth the name. Just a man, his land, and an endless procession of trucks carrying the effluvia of American industry.

You can read about this on New York’s Department of Environmental Conservation website: Click here.