How The Roman Catholic Church Attacked Albany, NY - Over and Over...

How Rome’s Outpost on the Hudson Perfected the Art of Holy Plunder

There’s a locked room in the chancery of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Albany that tells you everything you need to know about American Catholic power in decline. No gold chalices, no jewel-encrusted reliquaries, no illuminated manuscripts worthy of a Medici cardinal’s envy. Just filing cabinets. Rows and rows of filing cabinets documenting, with the meticulous bureaucratic precision that would make any Vatican functionary proud, which priests had violated which children, when, and how often.

Bishop Howard J. Hubbard kept the key for forty years. And when he finally died—having just married a woman in what can only be described as his final ecclesiastical middle finger to Rome—that locked room became the Rosetta Stone for understanding how an entire regional culture of Catholic institutions learned to operate: document internally, lie externally, and when the bill comes due, file for bankruptcy and blame the lawyers.

Because here’s the thing about Albany’s Catholic establishment that nobody wants to say out loud at the Wolfert’s Roost Country Club or over drinks at 677 Prime: the sexual abuse scandal wasn’t an aberration. It was a template. The same institutional muscle memory that allowed bishops to reassign pedophile priests while filing false reports with authorities also allowed them to loot a hospital pension fund while filing false reports with the IRS. The same boardroom reflexes that shuttered a 103-year-old college with seven months’ notice—leaving students mid-semester and faculty without severance—also allowed the region’s largest healthcare network to sue poor patients for medical debt while collecting millions in state funds earmarked to help those same patients.

Different institutions, same DNA. And at the center of it all, wearing the miter and carrying the crosier, stood Howard Hubbard—a man who, had he been running Enron instead of a diocese, would have died in federal prison rather than in his marriage bed.

THE BOY BISHOP AND THE ART OF LOOKING PROGRESSIVE

Howard Hubbard arrived in Troy, New York, in 1938 with the kind of pedigree that screamed “future cardinal”: St. Patrick’s School, La Salle Institute, off to Rome for the Gregorian University. The whole glittering cursus honorum of mid-century Catholic ambition. He was ordained in 1963, just as Vatican II was promising to modernize a Church that desperately needed modernizing, and he positioned himself as exactly the kind of bishop the new era demanded.

A “street priest” in Albany’s South End. Drug rehabilitation centers. Crisis intervention. He opposed the death penalty, championed social justice, lived in “monastic simplicity” while other bishops occupied baroque palaces. Liberals adored him. The New York Times loved him. When Pope Paul VI made him Bishop of Albany in 1977 at age 37—the youngest bishop in America—the press dubbed him “the boy bishop” and everyone agreed he represented The Future.

What nobody knew was that within months of his installation, the first child sexual abuse allegation would cross his desk. Or that his response would establish a pattern he’d follow for the next four decades: acknowledge nothing publicly, document everything privately, and treat anyone demanding accountability as an enemy of the Church.

By the time Hubbard faced his deposition in April 2021 he was 83 years old and facing seven active lawsuits alleging he’d sexually abused minors. The lawyer questioning him was Jeff Anderson, the Minneapolis attorney who has made a second career of extracting confessions from bishops who thought they’d never have to account for anything.

And what Anderson extracted was exquisite in its bureaucratic horror. Between 1977 and 2002, Hubbard acknowledged handling at least eleven cases of priests accused of child sexual assault. Eleven that he could remember, anyway. The procedure was consistent: remove the priest, send him to a Catholic treatment facility (there were several specializing in “troubled” clergy), get a clean bill of health from the in-house therapists, reassign him to a new parish where nobody knew his history.

And the parishioners at the new parish? What were they told about their new pastor?

“I’m not comfortable with the word disguised,” Hubbard said, with the careful precision of a man who’d spent a lifetime parsing language, “but we didn’t reveal fully why the person was removed.”

Not untruthful, you understand. Just not the full truth. A masterclass in ecclesiastical evasion.

THE VICE CHANCELLOR AND THE PRICE OF INNOCENCE

If you wanted a case study in how thoroughly Hubbard’s system had corrupted the institutional bloodstream, you need only look at Father Edward Charles Pratt.

Pratt wasn’t some obscure parish priest. He was the Vice Chancellor of the Albany diocese—Hubbard’s number two. He lived in the chancery. Under the same roof as the bishop. And according to court documents, he spent years sexually abusing children, including an eleven-year-old boy in state custody at St. Catherine’s Center for Children.

The diocese had received warnings about Pratt. In 1999, Hubbard finally sent him to Southdown, one of those Catholic facilities where priests with “issues” went for therapeutic tune-ups. The experts evaluated Pratt and delivered their verdict: he “still has issues with impulses to act out with youth.”

A reasonable person might conclude that someone with impulses to sexually abuse children should never work with children again. Hubbard concluded that Pratt’s work should be “supervised and adult focused.” As if pedophilia and sexually assaulting children was something to be managed rather than a crime to be prosecuted.

Pratt wasn’t finally removed until 2002, when the Boston Globe’s Spotlight investigation made business-as-usual impossible. By October 2025, on the eve of trial, the diocese agreed to pay his victim $8 million—the largest single payout in Albany diocesan history. Eight million dollars. The going rate, apparently, for one stolen childhood and four decades of institutional indifference.

But here’s where the story achieves a certain black-comic grandeur: Hubbard himself was accused by ten individuals of sexual abuse. The allegations stretched from 1977 to the 1990s. One involved a teenager whom Hubbard allegedly paid for sex. Another involved a young man who took his own life in 1978, leaving a note citing his abuse by “Howard” as the reason for his suicide.

Hubbard denied everything, naturally. Hired his own investigator— you read that right. He was allowed to pick the investigator. No police. A handpicked investigator and guess what this Colombo conveniently found - no credible evidence.

When the Child Victims Act reopened the cases, Hubbard petitioned Rome to be laicized—stripped of his priesthood—so he could escape with his pension intact.

Rome said no. Wait until the legal matters are resolved, they told him.

Hubbard was not a waiting kind of man. In August 2023, he announced he’d “fallen in love with a wonderful woman” and married her in a civil ceremony. The diocese declared the marriage invalid. Three weeks later, Hubbard had a massive stroke and died.

His funeral was presided over by Bishop Edward Scharfenberger, who praised the “much to celebrate” in Hubbard’s life while acknowledging he “was not an uncontroversial figure at times.” The alleged victims were not mentioned. It was, in its way, perfect: one last exercise in not telling the full truth.

THE PENSION FOR THE PREDATORS

If the sexual abuse scandal revealed Albany’s Catholic establishment could sacrifice children for institutional reputation, the St. Clare’s pension scandal proved they’d sacrifice anyone.

St. Clare’s Hospital in Schenectady was called “the People’s Hospital.” Founded in 1949 as a joint venture between the diocese and the Franciscan Sisters of the Poor, it served the community for nearly sixty years before being forced to close in 2008. The diocese donated the land. When it shut down, workers were assured their pensions were safe. The fund had received $28.5 million in Medicaid benefits specifically to keep it solvent.

They were not safe. In 2018, the pension plan was terminated with a $50 million shortfall. Of 1,124 retirees, approximately 650 would receive nothing. The rest got 70 cents on the dollar.

The mechanism was hauntingly familiar. According to New York Attorney General Letitia James, Bishop Hubbard and other diocesan officials filed false annual reports with the IRS claiming required pension contributions were being made. In reality, contributions were made in only two years between 2000 and 2019. The fund was hemorrhaging, and the people responsible were filing paperwork saying everything was fine.

Notice the parallel: With abused children, the diocese maintained internal files documenting which priests were predators while telling parishioners priests had been reassigned for “health reasons.” With the pension fund, the diocese maintained internal knowledge the fund was catastrophically underfunded while telling the IRS contributions were current. Same institutional reflex. Same willingness to file false statements. Different victims.

The diocese tried to disclaim responsibility. St. Clare’s Corporation was a separate entity, they argued. Never mind the corporate structure that gave the bishop control over everything that mattered.

A Schenectady County jury disagreed with the diocese’s claims of independence. On December 12, 2025, they found six defendants liable for breaching their fiduciary duties and awarded pensioners $54.2 million in damages: Joseph Pofit, the former St. Clare’s board president who was also a diocesan employee, bore 25 percent of the liability. Robert Perry, former St. Clare’s Hospital President, was assigned 20 percent. Bishop Howard Hubbard’s estate: 20 percent. St. Clare’s Corporation itself: 20 percent. Bishop Edward Scharfenberger: 10 percent. And Father David LeFort, the late diocesan vicar general: 5 percent. Punitive damages are still to come.

During the trial, evidence emerged of how Bishop Scharfenberger—the man who’d eulogized Hubbard’s legacy—regarded the hospital workers fighting for their retirement.

In text messages shown to the jury, Scharfenberger called the pensioners “predatory.” He warned staff they “are not friends.” He advised employees to be polite or simply “ignore them.”

Predatory. The word is worth savoring. Here was a bishop presiding over a diocese that had harbored actual predators for decades, applying that term to nurses and orderlies who wanted only to collect the retirement they’d earned. The linguistic inversion is so audacious it achieves a kind of terrible artistry.

THE COLLEGE THAT COULDN’T TELL THE TRUTH

The College of Saint Rose didn’t just close. It was conceived, born, and died within the institutional embrace of Albany’s Catholic establishment—a 103-year arc from diocesan vision to institutional abandonment.

The idea for the college came from Monsignor Joseph A. Delaney in 1920. Not a Sister. Not a lay Catholic philanthropist. The vicar-general of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Albany—the diocese’s number-two administrator. Delaney contacted the Sisters of St. Joseph of Carondelet with his plan. With “the permission and support” of Bishop Edmund F. Gibbons—language that makes clear who held authority—Delaney and the Sisters purchased the William Keeler estate.

When the college opened that fall, Bishop Gibbons was named honorary president. Contemporary accounts described it as establishing “the first Catholic woman’s college in the Albany Diocese.” Not a college in the diocese. A college of the diocese.

The Sisters ran Saint Rose for fifty years. In 1970, facing demographic pressures that would eventually kill the institution, the board was expanded to include laypersons. The college became “an independent college sponsored by the Sisters of St. Joseph.” Note the language: sponsored by, not controlled by. The shift suggests continued affiliation even as day-to-day operations passed to lay leadership.

By November 2023, it was educating approximately 2,600 students and hemorrhaging money at a rate that would have impressed a Wall Street short-seller.

The numbers were catastrophic: an $11.3 million projected deficit, accreditation in jeopardy, eight buildings listed for sale in August. And still, that September, the administration welcomed incoming freshmen. Still accepted tuition deposits. Still moved students into dorms and started classes, knowing full well the institution was circling the drain.

On November 30, 2023, while the women’s soccer team was in West Chester, Pennsylvania, losing a penalty shootout in the NCAA tournament, the Board of Trustees was in Albany voting to close the 103-year-old institution. The players learned their school was closing at approximately the same moment they learned their season was over.

That timing—accidental, absurd, almost poetic in its cruelty—captures everything about how Saint Rose handled its own death. Students found out from press reports before administrators could tell them. Faculty learned their jobs were gone with no severance, no continued health insurance, nothing. An entire neighborhood—87 buildings in Albany’s Pine Hills—went dark, and nobody had a plan.

“You guys welcomed me into this school, you gave me a scholarship, you promised me all this in my financial aid, and we’re broke,” said Asiarae Rivera, a freshman business major, with the unvarnished clarity of someone who’d just discovered that institutions lie.

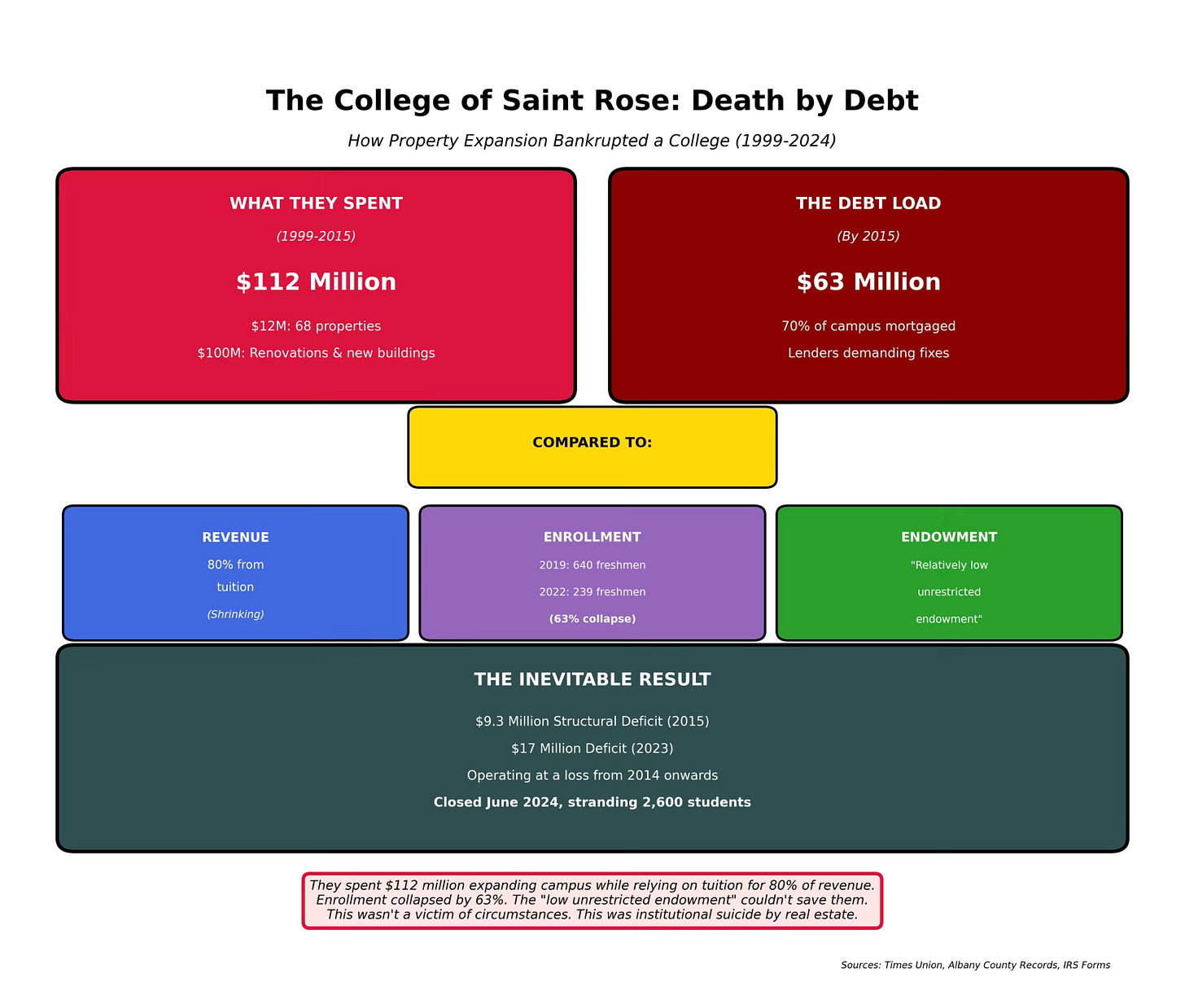

The college’s descent had been visible for years to anyone paying attention. Under President R. Mark Sullivan (1996-2012), Saint Rose spent more than $100 million on new facilities during what appeared to be a golden age. But the spending spree masked a fatal dependency: 80 percent of the budget came from tuition, in a region where high school graduates were declining year after year.

By 2014, President Carolyn Stefanco was informing faculty of an $18 million structural deficit and $56 million in long-term debt. Seventy percent of college property was mortgaged. She eliminated 40 staff positions, cut health benefits, reduced tuition remission. Then came the bloodletting: in 2015, Saint Rose eliminated two dozen academic programs and laid off 23 faculty members, including tenured professors.

The American Association of University Professors investigated and found the administration had excluded faculty from deliberations, ignored their objections, and rendered tenure “virtually meaningless.” The AAUP censured Saint Rose—a designation it still held when the college closed.

Stefanco resigned under pressure. The bleeding continued. In 2020, Saint Rose cut 25 more programs and 41 more faculty jobs. Enrollment collapsed from 4,000 students before the pandemic to 2,600 by 2023. The accreditor warned in June that accreditation was “in jeopardy.”

And still, the administration kept recruiting. Still welcoming freshmen who’d taken out loans, made plans, moved to Albany—only to discover mid-semester that the institution they trusted had been hiding its terminal diagnosis.

The final commencement was held in May 2024. The last day of instruction was June 21. One hundred and three years of history, ended in seven months. Six hundred and forty-six employees shown the door. When faculty asked about severance, Board Chairman Jeffrey Stone delivered the news with bureaucratic precision: there was no money. The college would “expend nearly all its cash resources, including its unrestricted endowment, by June 30.”

Nothing left to give. Not to faculty who’d devoted decades to the institution. Not to adjuncts already among the most precarious workers in higher education. Certainly not to the students who’d believed the marketing materials.

The college’s 87 properties sat empty through an entire winter. Local businesses lost a significant chunk of their customer base overnight. Junior’s restaurant, the Madison Café—all watching their revenue streams dry up while the county fumbled toward a plan for what comes next.

Albany County eventually purchased all 91 parcels for $35 million, nearly a year after the closure. The plans are still taking shape. What remains certain is that the administrators made choices—to spend lavishly in boom years, to mortgage 70 percent of campus, to rely on tuition for 80 percent of revenue, to keep recruiting students even as the building burned. They chose to exclude faculty from deliberations. They chose to offer no severance. They chose, until the very end, to project optimism while everything collapsed.

In October 2024, Saint Rose filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy—the legal process of disposing of a corpse. The college’s website still exists, a digital ghost, assuring visitors that its “mission and values” will “live on through the work and lives of its alumni.”

Missions and values, alas, don’t pay rent or provide health insurance. But they do make excellent epitaphs.

ST. PETER’S AND THE POOR

In 1863, four Religious Sisters of Mercy arrived in Albany with eighty cents between them—about nine dollars in today’s money. They came to care for the sick, the poor, and the dying. Within six years, thanks to Peter Cagger purchasing land “for the Roman Catholic Diocese of Albany,” they’d founded St. Peter’s Hospital with a mission of “lessening human suffering and saving life.”

One hundred and fifty-five years later, St. Peter’s Health Partners is the Capital Region’s largest private employer, with 11,000 workers spread across 185-plus locations. It operates the largest Catholic acute care hospital in northeastern New York. It has won awards for cardiovascular care and nursing excellence. It is, by any measure, a pillar of the community.

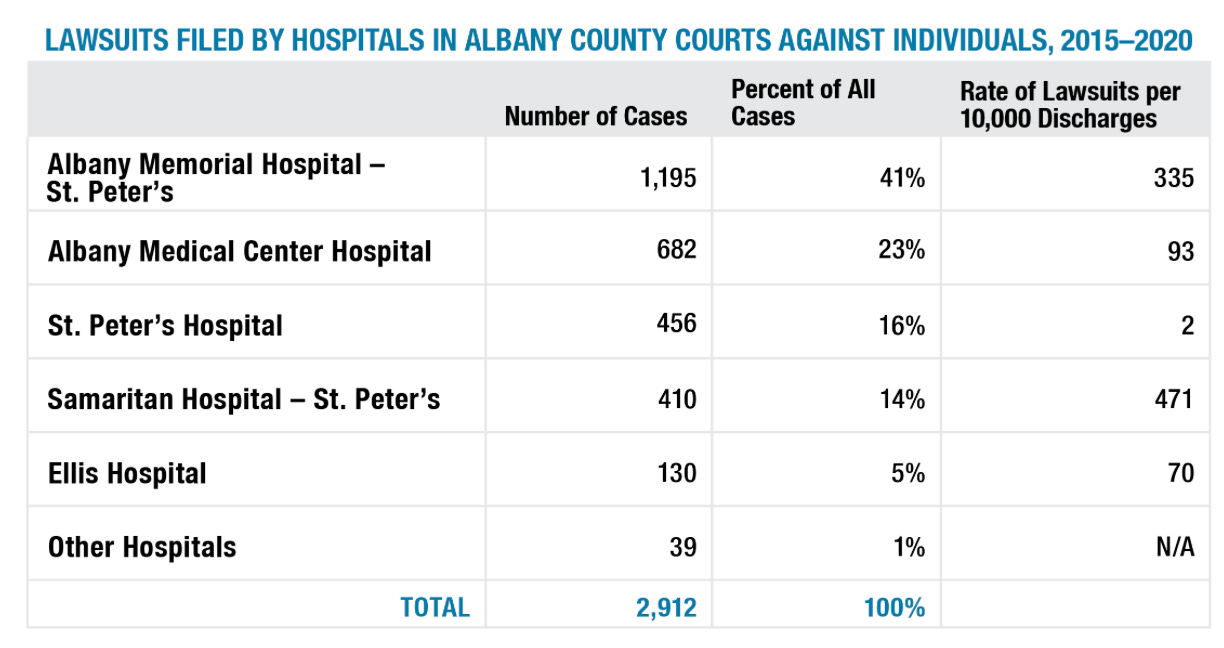

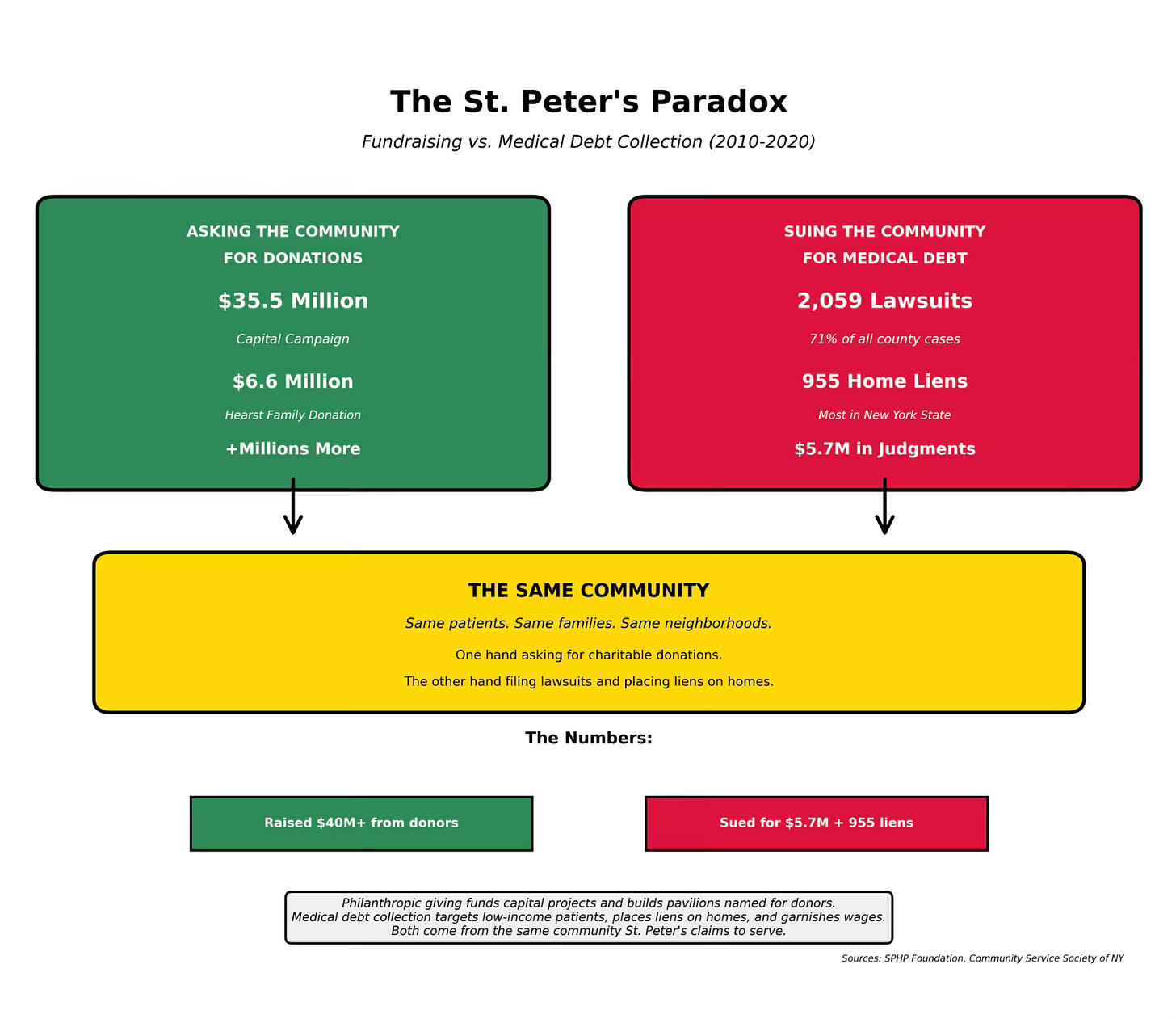

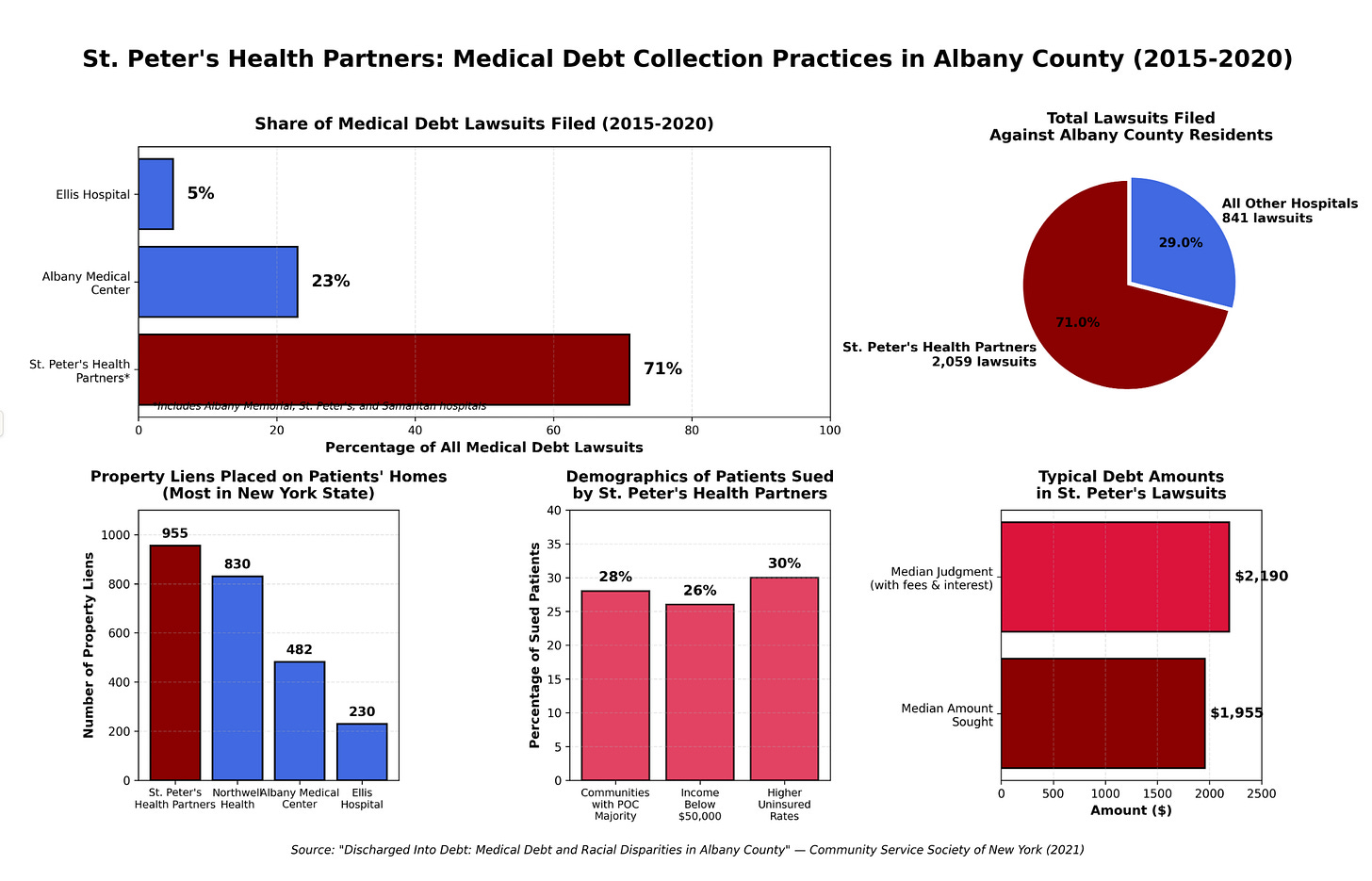

It also, according to the Community Service Society of New York, filed 71 percent of all medical debt lawsuits in Albany County between 2015 and 2020. It placed more liens on patients’ homes than any hospital system in New York State. And it continued suing patients throughout the COVID-19 pandemic—571 lawsuits between March and December 2020 alone, while the once-in-a-century plague raged and people lost jobs, lost income, lost their lives.

The Sisters of Mercy arrived with eighty cents and a mission to serve the poor. The institution they built now takes the poor to court over debts averaging $1,955.

The numbers, compiled by the Community Service Society, are staggering in their precision. Between 2015 and 2020, five nonprofit hospitals sued 2,900 Albany County residents for unpaid medical bills. Three of those hospitals—St. Peter’s, Albany Memorial, and Samaritan—belong to St. Peter’s Health Partners. Together, they accounted for 71 percent of all lawsuits.

Albany Memorial Hospital alone filed 1,195 lawsuits during this period. The median amount St. Peter’s Health Partners sought was $1,955. The median judgment, after court fees and the statutory 9 percent interest rate, was $2,190. These aren’t wealthy people refusing to pay luxury medical bills. These are fast-food workers, retail employees, people in industries where wages barely cover rent, being hauled into court over amounts that, to a major hospital system, represent rounding errors.

And the impact falls precisely where you’d expect. According to the CSS analysis, 28 percent of sued patients live in communities where the majority are people of color. Twenty-six percent live in communities where median household income is below $50,000. Thirty percent live in communities with uninsured rates higher than the state average.

“People of color are two to five times more likely—250 percent more likely—to have medical debt than white people” in Albany County, Elisabeth Benjamin of CSS told CBS6. The aggressive litigation practices of these hospitals, she concluded, “is what is driving the profound racial disparities in medical debt in Albany County.”

But filing lawsuits is merely the opening move. When St. Peter’s wins a judgment and files a lien on someone’s home, that patient generally cannot sell, refinance, or take out a home equity loan without first paying the debt. If your pipes burst in winter, you can’t borrow to fix them. The lien sits there, accruing interest, a legal encumbrance that follows the property until the debt is satisfied or you lose the house entirely.

St. Peter’s Health Partners placed 955 liens on patients’ homes over the study period—more than any other hospital system in New York State. Northwell Health, the second-highest, placed 830 liens before stopping the practice entirely in 2019 after CSS began investigating. Albany Medical Center placed 482. Ellis Hospital placed 230.

The hospitals insist litigation is a “last resort” employed only after other collection attempts fail. St. Peter’s spokesperson Robert Webster said the system “considers each patient on a case-by-case basis and has exceptions in place for low-income and uninsured patients.” The hospital provides financial assistance to eligible patients, he noted.

But New York law already requires hospitals to offer financial assistance to uninsured patients with incomes below 300 percent of the federal poverty line—roughly $52,000 for a household of two. The fact that so many patients living in low-income communities are being sued suggests either the law isn’t working or the hospitals aren’t implementing it as aggressively as they might.

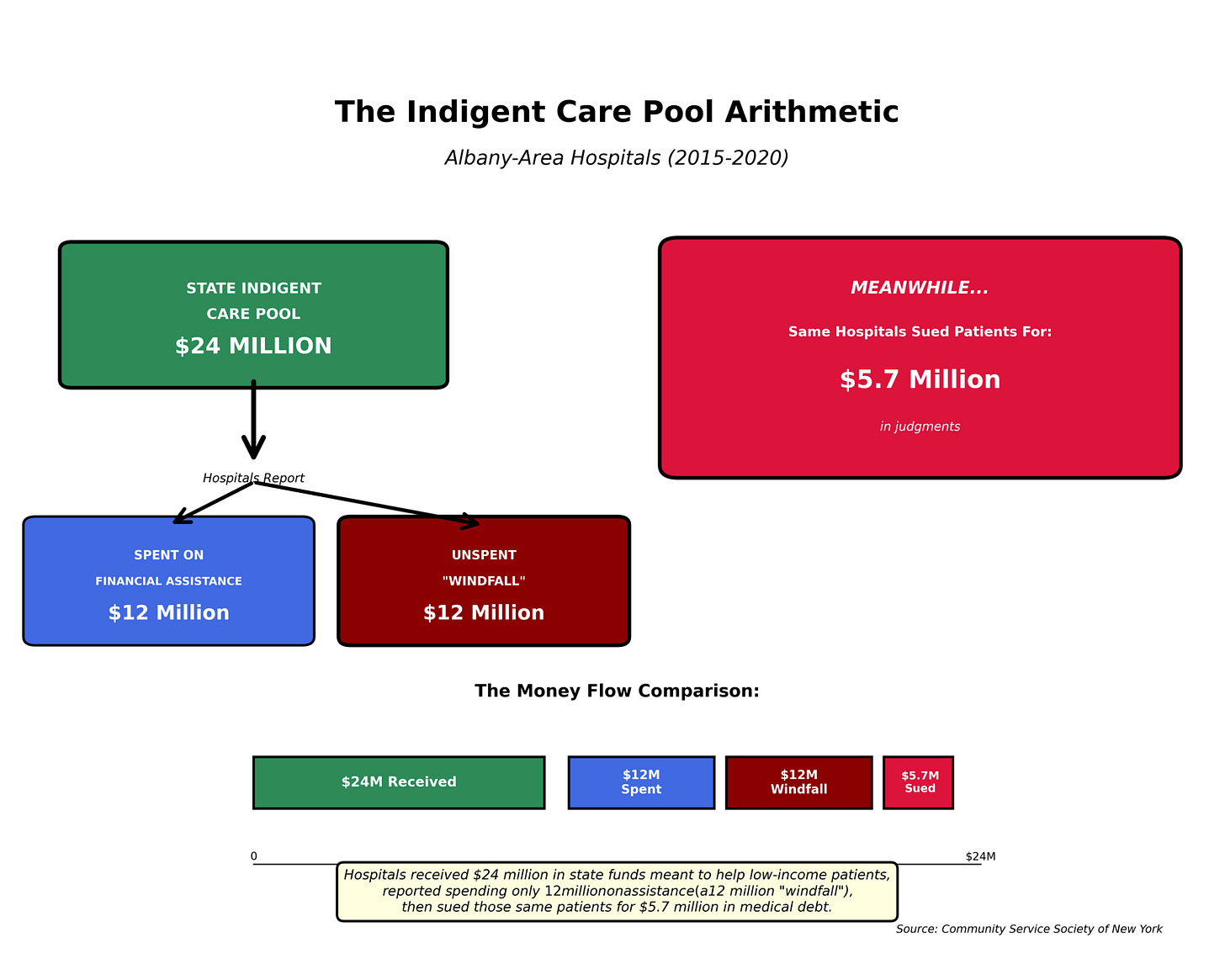

Here’s the telling arithmetic: During the same period Albany-area hospitals were suing patients for an estimated $5.7 million in total judgments, those same hospitals received roughly $24 million from the state’s Indigent Care Pool—funds specifically designated to offset uncompensated care costs and encourage financial assistance to low- and moderate-income patients. The hospitals reported spending only $12 million on such assistance, creating what CSS described as a “one-year windfall of $12 million.”

More than double what they sought in court from the patients they were supposedly too poor to help.

Medical debt collection, however, is not St. Peter’s only creative revenue strategy. In 2006, two Albany nurses filed a federal class-action lawsuit against six Capital Region hospitals, including St. Peter’s and Albany Medical Center, alleging something far more serious: a conspiracy to fix wages.

According to the lawsuit, human resources employees at the hospitals “regularly telephoned each other” to determine what competing institutions were paying registered nurses, including scheduled increases. These “information exchanges” became more frequent at fiscal year-end, when hospitals were drafting budgets. The result, the lawsuit alleged, was that hourly rates paid by the hospitals differed by no more than one dollar—a remarkable uniformity in what was supposed to be a competitive labor market during a nationwide nursing shortage.

The lawsuit described the alleged conduct as a “wage-fixing conspiracy” that kept “compensation for hospital RN employees in the Albany area at artificially low levels.” It also alleged the conspiracy forced hospitals to “under-utilize RNs, yielding low nurse-to-patient ratios, forcing RNs to work harder for longer hours and reducing patient quality of care.”

The nurses’ attorney estimated each nurse lost approximately $6,000 per year. The lawsuit covered 4,060 nurses. St. Peter’s settled in June 2009 for nearly $2.7 million. Northeast Health settled for $1.25 million. Albany Medical Center, the last major defendant standing, settled in February 2011 for $4.5 million. Total settlements exceeded $9 million.

All defendants denied wrongdoing, naturally. They settled, they said, “to limit the expense and distraction of additional court proceedings.” Which is what institutions always say when they’re paying millions to make allegations of federal antitrust violations disappear.

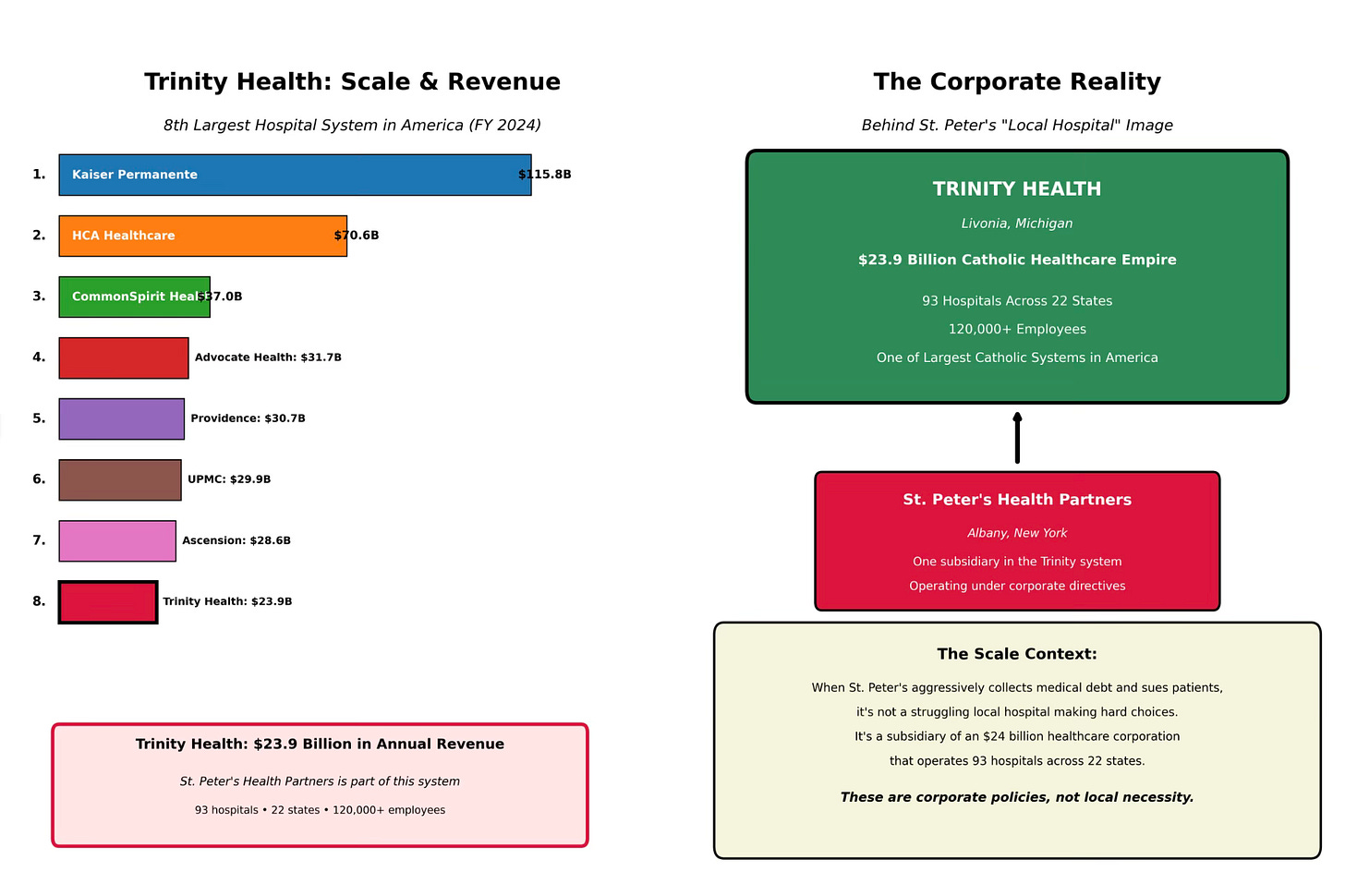

St. Peter’s Health Partners is a member of Trinity Health, one of the nation’s largest Catholic health systems, operating hospitals in 22 states. The organization’s stated mission is to serve “in the spirit of the gospel as a compassionate and transforming healing presence within our communities,” with particular emphasis on “the needy and vulnerable.”

The Catholic tradition from which St. Peter’s emerged has strong teachings on economic justice. The principle of the “preferential option for the poor”—the idea that Christians have a special obligation to prioritize the needs of the marginalized—runs through papal encyclicals and bishops’ letters. The Sisters of Mercy who founded St. Peter’s Hospital were following Catherine McAuley, who established the first House of Mercy in Dublin in 1827 specifically to serve the sick poor.

There is, to put it mildly, some tension between that tradition and a business model involving 955 property liens over $2,000 debts.

The hospitals would argue—and do argue—that they cannot simply write off all unpaid bills, that they have employees to pay and equipment to maintain. They would note they offer financial assistance to those who qualify. They would point out the lawsuits represent a tiny fraction of total patient encounters.

All of which may be true. But it doesn’t explain why St. Peter’s Health Partners files more lawsuits than any other regional system. It doesn’t explain why Albany County is a medical debt litigation hotspot while other communities with similar demographics are not. It doesn’t explain why a Catholic hospital network with $24 million in state indigent care funding finds it necessary to place 955 liens on patients’ homes.

Other institutions have made different choices. Northwell Health stopped suing patients for back debt entirely after the CSS reports began drawing attention. Some hospital systems have adopted policies against placing liens on primary residences under any circumstances. These are choices, not inevitabilities—and St. Peter’s has, so far, chosen differently.

The Sisters of Mercy arrived with eighty cents and built something extraordinary—a healthcare system that has served the Capital Region for more than a century and a half. But somewhere along the way, the institution they built forgot what it was for. Somewhere along the way, “lessening human suffering” became compatible with placing liens on the homes of fast-food workers over two-thousand-dollar debts. Somewhere along the way, caring for the poor became consistent with suing them.

The Sisters might not recognize what their legacy has become. The patients being sued certainly don’t.

THE PATTERN

What connects a bishop who covered up child sexual abuse, a pension fund looted while false reports went to the IRS, a college that recruited students knowing it would close, and a hospital system that sues poor patients while collecting state funds meant to help them?

It’s the same institutional muscle memory Albany’s Catholic establishment has perfected over decades: Document internally, lie externally, prioritize institutional survival over human welfare, and when consequences arrive, file for bankruptcy and claim victimhood.

On March 15, 2023, the Roman Catholic Diocese of Albany filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection, becoming the fifth of New York’s eight dioceses to seek shelter from Child Victims Act claims. Bishop Scharfenberger announced the filing with the air of a man who’d reluctantly concluded all options were exhausted. There was simply no more money, he said, to settle the remaining 400-plus abuse claims.

Suddenly abuse survivors and defrauded pensioners found themselves in the same legal queue, competing for slices of the same diminished pie. Insurance companies began objecting to claims. Mediations stalled. The meter kept running on legal fees—over $11 million and counting in the Baltimore archdiocese bankruptcy, with survivors there still waiting to receive a penny.

The convergence of the two victim groups in bankruptcy court is not coincidental. It’s the logical endpoint of the Church’s management philosophy. Betray children, betray workers, document it all internally, lie to everyone externally, and when the bill comes due, declare insolvency and let the victims fight over scraps. Bankruptcy becomes not a last resort but the final move in a four-decade strategy of evasion.

U.S. Bankruptcy Judge Robert E. Littlefield Jr., presiding over the Albany case, hasn’t hidden his frustration. “Time is fleeting, life is fleeting, and all I do is approve fees,” he said at one hearing. “What is the alternative? An endless number of days gone by before there is anything accomplished. That is the frustrating part.”

In September 2025, approximately fifty survivors delivered victim impact statements in the Albany federal courthouse. For three days, the bankruptcy proceeding paused its endless procedural machinations to do something it hadn’t done before: listen.

“I am now 80 years old,” one survivor testified. “I think about it every day and every night.”

“I felt like I was drowning with God himself forcing me under water,” said another.

Many were children in the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s. They’re now in their sixties, seventies, and eighties. They’ve lived entire adult lives with wounds that never healed, trusting in a system that proved unworthy of their trust, waiting for accountability that’s only now, imperfectly, arriving.

Attorney Cynthia LaFave, who represents 190 survivors, spoke of another group: “We also represent people who died without knowing that there is any justice given to them for what they suffered. And that is something that we carry with us as well.”

The pensioners have their dead too—retirees who spent their final years in financial anxiety, who scrimped and worried and did without, who never saw the verdict that vindicated their claims. Both groups of victims, the abused children and the defrauded workers, share this grim distinction: the institution outlasted many of the people it harmed.

THE DEFENSE OF SEPARATE ENTITIES AND FALSE EQUIVILENCIES

What Bishop Scharfenberger will tell you is that these are separate institutions. The diocese didn’t run Saint Rose. St. Peter’s is part of Trinity Health. St. Clare’s Corporation was its own entity.

All technically true, in the way that claiming the Oval Office and the West Wing are separate buildings is technically true. The question isn’t architecture. It’s control.

St. Clare’s bylaws tell the story. The sitting Bishop of Albany was an automatic board member and Honorary Chairman. He had sole power to appoint the board Chairman, approve every board member, veto director selections, approve all executive hires, and control property disposition. Upon dissolution, all assets would accrue to the Bishop.

This is not independence. This is a wholly-owned subsidiary with extra steps.

The operational reality matched. After St. Clare’s closed, the hospital and diocese shared the same address: 40 North Main Avenue, the diocesan pastoral center. Joseph Pofit, St. Clare’s board president, was a diocesan employee conducting business from the pastoral center with diocesan staff. When asked about reporting structure, St. Clare’s Hospital President Robert Perry testified the Bishop was “his boss.”

In May 2008, Bishop Hubbard disbanded the entire board, leaving himself as sole director. During this period of exclusive control, the pension plan lost over $6 million. When asked what steps he took to monitor the plan, Hubbard could not identify a single action.

On December 12, 2025, a Schenectady County jury awarded $54.2 million in damages.

The College of Saint Rose was conceived by Monsignor Joseph A. Delaney, the diocesan vicar-general, with “the permission and support” of Bishop Edmund F. Gibbons. When it opened in 1920, Bishop Gibbons was named honorary president. Contemporary accounts called it “the first Catholic woman’s college in the Albany Diocese.” Not a college in the diocese. A college of the diocese.

St. Peter’s Hospital opened in 1869 on land purchased “for the Roman Catholic Diocese of Albany.” Today it operates as part of Trinity Health—the diocesan connection is ceremonial. Of the three institutions, St. Peter’s has traveled furthest from direct diocesan control. But it began under diocesan authority, on diocesan land, structured to serve the Church’s mission.

Here’s what connects them: each began under diocesan authority, and each reveals the same institutional reflexes.

St. Clare’s knew internally the pension fund was catastrophically underfunded while filing IRS reports claiming contributions were current. Saint Rose recruited freshmen in fall 2023 while the board knew the institution wouldn’t survive the year. St. Peter’s sues poor patients while collecting millions in state funds meant to help those patients. The diocese maintained files on predatory priests while reassigning them to new parishes.

The defense of separate entities requires us to believe these parallel pathologies developed independently. That St. Clare’s board members—appointed by bishops, reporting to bishops, meeting in the diocesan building—somehow absorbed none of the diocese’s institutional culture.

The jury in Schenectady didn’t buy it. Neither should anyone else.

And when this defense crumbles, diocesan spokesmen pivot: yes, but look at all the good we do. Catholic Charities serves thousands - provides addiction treatment. Catholic schools educate children.

All true. All admirable. All utterly irrelevant.

This is moral arithmetic as practiced by fraudsters: pile enough good deeds on one side of the ledger and maybe no one will notice the staggering harm on the other. The flowers don’t cancel the bruises. The soup kitchen doesn’t absolve the cover-up.

Catholic Charities’ work doesn’t erase the $54.2 million stolen from St. Clare’s workers. School lunch programs don’t resurrect Saint Rose. Addiction counseling doesn’t remove the 955 liens St. Peter’s placed on patients’ homes. And none of it makes Father Pratt’s victims whole again.

This is more than false equivalency. It’s premeditated distraction. A rhetorical sleight of hand designed to move your eyes from the crime scene to the charity gala. Don’t look at the children we failed to protect—look at the children we’re feeding. Don’t examine the pensions we plundered—admire the jobs we created.

The good work is real. So is the harm. They don’t cancel each other out. They exist simultaneously—which is precisely the problem. These are institutions sophisticated enough to run effective social service programs and maintain detailed files on predatory priests. Organized enough to coordinate healthcare networks and systematically underfund pension obligations. Capable enough to educate thousands of students and recruit hundreds more into an institution they knew was dying.

That’s not contradiction. That’s institutional capacity deployed selectively. They can do the work when it serves them. They simply choose not to when it doesn’t.

The defense of separate entities is the playbook, scaled across an entire regional Catholic establishment: document internally, lie externally, and when consequences arrive, point to the corporate veil and claim independence. When that fails, point to the soup kitchen and claim redemption.

It’s not untruthful, just not the full truth.

THE TWO-TIERED SYSTEM

Think what would have happened if Howard Hubbard and the leadership had been the CEO and board members of a Fortune 500 company rather than “men of the cloth.”

Imagine a company whose executives knowingly employed serial child abusers, documented the abuse internally, moved abusers to new locations when complaints arose, and lied to regulators about personnel reassignments. The executives would face federal charges. Conspiracy to obstruct justice. Racketeering. Possibly charges under laws prohibiting transport of minors across state lines for illegal purposes.

Now imagine the same company, run by the same executives, operated a pension fund it systematically looted, filing false annual reports with the IRS claiming contributions had been made when they hadn’t, until the fund collapsed and over a thousand retirees lost everything. That’s federal tax fraud. ERISA violations. Wire fraud for every electronic communication involved in the scheme. The Department of Labor would be involved. The FBI would be involved. Grand juries would be issuing indictments.

Bernie Madoff died in federal prison for running a Ponzi scheme. Elizabeth Holmes is serving eleven years for lying to investors about her company’s technology. Jeffrey Skilling served twelve years for Enron. The executives of these companies did not have access to sacred vestments or centuries of institutional deference.

Howard Hubbard acknowledged under oath that he concealed information about child-abusing priests from parishioners and law enforcement. The diocese he led filed, according to the Attorney General, false annual reports to the IRS about pension contributions. He presided over an institution that systematically protected predators and defrauded workers.

He was never charged with a crime. He died a bishop, having just married the woman he loved in a final act of ecclesiastical defiance.

The disparity demands explanation. Part of it is structural: religious organizations enjoy deference from prosecutors reluctant to appear anti-religious. Part of it is practical: statutes of limitations had expired on many abuse-era crimes. Part of it is political: no district attorney wants to be the person who put a bishop in handcuffs.

But part of it is simply that we’ve decided, as a society, that religious institutions operate under different rules. When a CEO lies to regulators, we call it fraud. When a bishop lies to regulators, we call it a “failure of leadership” and let bankruptcy courts sort out the civil liabilities. When a company enables systematic child abuse, we expect criminal prosecutions of everyone who knew. When a church enables systematic child abuse, we expect apologies, settlements, and reforms—but rarely prison time.

This is not accountability. This is a two-tiered system of justice in which the collar protects against consequences that would destroy anyone else.

THE LOCKED ROOM

Back to that locked room in the Albany chancery.

What was in those files? We may never know the full contents. But we know what they represented: a systematic effort to document wrongdoing while concealing it from everyone who had a right to know. The police who might have investigated. The parishioners whose children were at risk. The families who trusted the Church with the most precious thing they had.

Howard Hubbard acknowledged under oath that he reviewed those files “when there was a report of misconduct on the part of a priest... to see if there was anything prior that would substantiate a report that I received.”

The files weren’t created to facilitate justice. They were created to manage risk—to the institution, not to children.

And somewhere in diocesan financial offices, there were records showing the St. Clare’s pension fund was being systematically starved while reports to the IRS claimed otherwise. Same logic. Same priorities. Same willingness to sacrifice real people for institutional convenience.

This is what institutional betrayal looks like. Not necessarily malice, though malice may be present. What it looks like, most often, is a set of priorities so warped that protecting the institution becomes indistinguishable from protecting the predators it harbors and the schemes it runs.

Father Gerard McGlone, a Jesuit priest and psychologist who’s studied the Church’s abuse response, reviewed Hubbard’s testimony and found himself asking: “How is it that his response mirrors and mimics all the other bishops’ responses at that point in time? It reeks of a common response.”

A common response. A playbook. A way of doing business that prioritized the institution over the innocent, reputation over truth, the collar over the law.

The locked room is open now. The files have been examined. The testimony has been taken. The verdicts are coming in.

It’s not justice, exactly. Justice would require turning back time, restoring childhoods, giving back retirement years spent in poverty, undoing what cannot be undone. Justice would require prison cells for the men who made it all possible.

What we have instead is accountability—civil, financial, incomplete, decades too late, but accountability nonetheless.

As one survivor told the bankruptcy court: “Religious organizations are supposed to be a source of support, not exploitation.”

The Albany Diocese failed that test—with children, with workers, with patients, with students, with anyone who trusted it to act with basic integrity. The pattern held across decades and institutions: know the truth, bury the truth, file false reports, protect the institution, and when finally cornered, seek bankruptcy protection while calling your victims “predatory.”

What would Jesus do? I don’t know. But I know what I’d do: make them pay taxes and put the bad actors in prison.

Increasingly, I’m convinced that religion has no place in public works. In our public schools and government, it’s been a disaster—zero transparency from entities that serve the public and spend public dollars. These institutions operate in the civic sphere while claiming the privileges of the sacred.

So yes, let’s leave Jesus home. Let him stay at church or in private schools, tending to his flock. But when religious institutions take public money, treat public patients, educate the public’s children, and employ the public’s workers, they must answer to the public—not to canon law, not to Rome, and not to the conscience of bishops who’ve proven they have none.

So, maybe you’re asking how this could have happened? All this bad behavior going unchecked. How? How does this happen? Good question.

Many, many people knew what was going on. There were complaints made. There were settlements, some that involved insurance companies. There were board meetings at St. Rose. St. Peter’s lawsuits are public record. St. Claire’s as well. But it doesn’t really answer the fundamental question. Why did it take The Boston Globe’s Spotlight to expose three decades of abuse in Albany, NY? Why was the closing of St. Rose such a shock? How did a community of nurses and hospital staff get screwed out of their pensions? How does a hospital founded on the principle of charity and healing the poor reconcile their collection practices to their mission?

What’s missing in this community?

Well, I’ve got some ideas. I’ll share them in Friday’s “This Week and Next” column.

If you have ideas—I’d love to hear them. Josh@thepowellhousepress.com

©2025 The Powell House Press All Rights Reserved.

Contact: josh@thepowellhousepress.com