The Grapes of Wrath: A Plastic Surgeon, a Vanity Vineyard, and the Dirt-Road Rebellion of Columbia County

A Small Town Versus the Plastic Surgeon Come Vintner

Columbia County lies in New York’s upper Hudson Valley, bordered by the Hudson River to the west and the Berkshire foothills to the east. The Town of Chatham occupies the county’s eastern portion near the Massachusetts border, encompassing several distinct hamlets: Chatham village serves as the commercial center, with a walkable main street and the historic Crandell Theatre; East Chatham stretches toward the Taconic Range along rural roads; Old Chatham is known for its horse farms and the Old Chatham Country Store; Malden Bridge sits quietly along the Kinderhook Creek in the town’s northeastern corner; North Chatham follows Route 203 through traditional farmland; and Chatham Center marks a small crossroads between the village and Old Chatham. The area remains a mix of working agriculture and newer residential development, with local planning boards regularly weighing questions of growth and preservation.

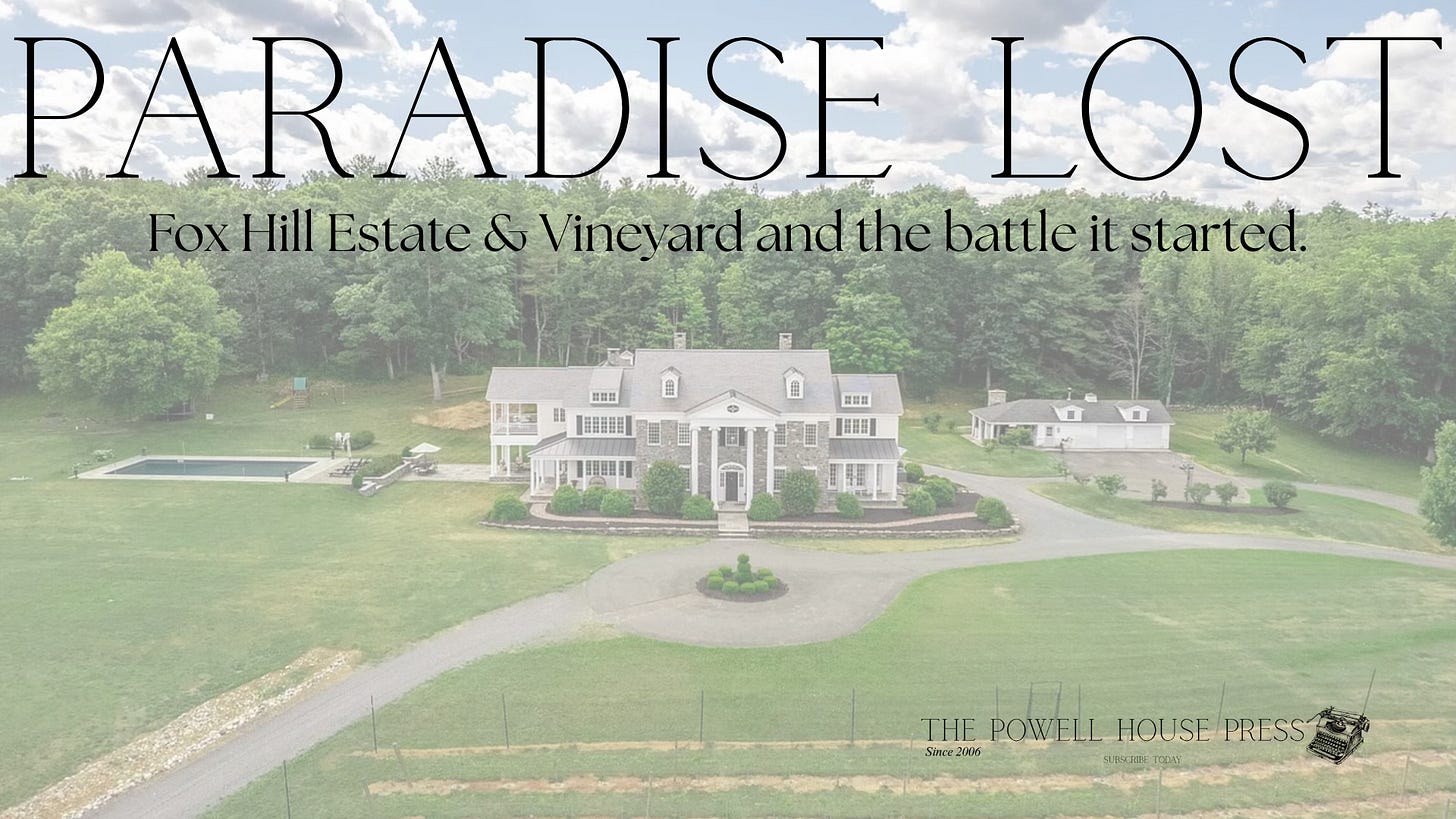

You see it in the house first—the stone façade, the climbing pillars, the architectural aspiration bellowing from the hilltop like a desperate personal ad. Look at me. LOOK AT ME. Some would say it screams money. Some have said it screams bad taste. In Columbia County, New York, where understatement was once considered a virtue and the old families built their farmhouses to weather quietly into the landscape, the Williams residence at 509 Bashford Road makes a different kind of statement entirely. It is the built equivalent of a man who tells you within five minutes of meeting him that he loves Paris in the spring and skiing in Gstaad.

Dr. Edwin Williams is a facial plastic surgeon—a professional improver of God’s rough drafts. His wife Cherie runs the business side of his practice. Together they have spent five years attempting to transform their 53.7-acre estate—assessed at a casual $3.75 million—into something called Fox Hill Estate & Vineyard, complete with tasting room, gravel parking lot, and the unmistakable infrastructure of a party palace in waiting. That they chose to name their venture after an already-existing Fox Hill down the road tells you everything about their relationship to originality. The neighbors, who moved to this corner of Chatham precisely because Bashford Road is unpaved, private, and perfect to hack out on your horse, were not consulted. This is horse country after all. It is also a tight community. News travels fast.

Starting January 1st, 2026, most of my work moves behind a subscriber paywall.

Right now, you can lock in a year for $35—or $5/month. After January 1st, the annual rate rises to $50.

I grew up there—on Richmond Road, which ends right at the foot of the proposed Fox Hill Estate & Vineyard. In the 1960s and ‘70s, while my contemporaries in Albany were learning whatever it is city kids learn, I was learning about the land, about farm animals, about the particular quality of silence you can only find where the roads are still dirt, and the horses still have the right of way. The Spencers were my neighbors then—dear family friends who lived on Bashford Road directly across from the Williams property.

Some residents wonder what their quiet lives might be like if this modern-day “Falcon Crest” comes to fruition. But I’ll get to them—and to my own history with Ed Williams, which involves a Facebook argument about hydroxychloroquine that revealed more about his character than any planning document ever could.

In my late forties, I moved back to the area, ironically buying a house on Fox Hill Road where my neighbors own Fox Hill Farm and commissioned a tasteful sign to say so. The Williamses couldn’t even be bothered to consult us before naming their vanity project. It was a concern because my road (and yeah, I owned the whole road) would be mistaken for their venue. How many potential couples from Brooklyn checking out wedding venues would type “Fox Hill Chatham” into their weekend-only Range Rover’s GPS and plow up my road? But nomenclature theft, it turns out, is the least of their offenses.

The origin story tells you everything. As one neighbor informed the Planning Board, The Williams’s interest in turning their property into a wedding venue first surfaced publicly on Cherie Williams’s Facebook page about 5 years ago. Their neighbors were not happy and expressed their concerns. Friends and neighbors were shocked at Ed and Cherie’s callous indifference. Note the sequence: announce your plans on Facebook, dismiss the objections of everyone who actually lives there, proceed as if consensus were a quaint irrelevance.

In 2019, Fox Hill Estate began advertising as a Wedding Venue; the website was removed a few years ago. It seems the Williamses’ saw the writing on the wall and in 2020 grape vines were planted. Why? To use NYS Agriculture and Markets Laws for the newest incarnation of the wedding venue: a wine tasting room. First the dream of becoming Columbia County’s answer to a Hamptons party barn. Then, when the zoning proved inconvenient, the agricultural fig leaf. Plant some grapes, call yourself a farmer, and Andy Cohen shows up with his cameras and posse of tacky housewives from the nearest franchise. It is a strategy familiar to anyone who has watched the wealthy discover that money can usually find a loophole.

The initial application proposed weddings for 100 to 150 guests. Peter McKenna, a retired farmer who actually knows what farming looks like, reminded the board what that original vision promised: “When the Williams first advertised their property as a wedding venue 4 years ago, the Fox Hill wedding site trumpeted that once the dancing started, partying could continue to the wee hours.” Partying to the wee hours. On a dirt road. In horse country. Where people moved specifically to escape noise.

When that proposal died on the vine, pun intended (the Williams let it age out), there was a sigh of relief.

It was short lived.

They returned with another application - something “scaled back”—a tasting room in a converted 700-square-foot garage, fifteen events per year, fifteen to twenty guests (though other documents mention forty), portable restrooms, disposable cups. The modesty is tactical, of course. Everyone in Chatham recognizes the playbook. You approve the tasting room, and suddenly the tasting room needs a kitchen. The kitchen needs a patio. The patio needs a tent for overflow. Before you know it, you’re living next to a destination wedding factory, and the Planning Board is explaining that their hands are tied because the original approval didn’t specifically prohibit amplified renditions of “I Gotta Feeling” at midnight.

Douglas Welch, president of the Chatham Dirt Road Coalition, has seen this movie before: “This special use permit has no enforcement capacity. The applicant’s claimed intent to limit the special events to 6 per year should be taken cautiously. Should tempting profitable opportunities arise for 7, or 8, or more large events, what recourse do their neighbors have?”

One resident asked, “Who will ‘shut down’ their seventh event?” The answer, of course, is no one. No one ever shuts down the seventh event.

The application file makes for riveting reading—if your taste runs to the spectacle of ambition colliding with bureaucratic reality. The town’s consulting engineer issued a review in October 2025 that catalogs everything the applicants have failed to provide: written responses to comments from the Planning Board, from neighbors, from consultants. Site plans showing existing features. Mapping of potential wetlands and the 100-foot buffer zones. Five years into this saga. Five years. And the applicants still haven’t done the basic homework.

But let’s talk about what they are proposing to do to the land—because the bucolic imagery of a vineyard tends to obscure some deeply inconvenient realities about what commercial grape cultivation entails.

Vineyards are not the pastoral enterprises the Williamses would have the Planning Board or the community believe. They are chemical-intensive agricultural operations that require repeated applications of fungicides, pesticides, and herbicides throughout the growing season. Grapes are notoriously susceptible to fungal diseases—powdery mildew, downy mildew, botrytis bunch rot. In Columbia County, where humid summers create ideal conditions for these pathogens, vintners typically spray fungicides every seven to fourteen days from bud break through veraison. That is not occasional treatment. That is a recurring chemical regimen spanning months.

The fungicides commonly used in viticulture—compounds like sulfur, copper-based products, synthetic organics—do not stay neatly on the grapes. They drift on the breeze. They settle on neighboring properties. They run off with rainwater into soil and streams. And where, exactly, does that runoff go? Toward the wetlands that sit at the base of the Williams hill. The wetlands that have not been properly mapped. The wetlands for which no jurisdictional determination has been obtained from the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation.

Neighbors have raised the alarm. Lisa and Gary Seff highlighted “the presence of NYS Regulated Wetlands, a DEC designated Check Zone, and Federal Wetlands (National Wetlands Inventory)” on portions of the property. Karen McGraw questioned “the impact on the stream and wetlands located at the base of the hill and questioned inaccurate information contained in a Short Environmental Assessment Form submitted by the Williams.” Another resident observed that “a parking lot is planned very near wetlands, in a residential neighborhood and in view of neighbors.”

Wetlands in New York are regulated for very specific reasons. They control flooding by absorbing runoff. They filter pollutants from water before it enters streams and aquifers. They provide critical habitat for wildlife. They are, in effect, nature’s own water treatment system. And the Williamses are proposing to put a parking lot, a commercial operation, and a chemically-intensive vineyard on the hill above them—without bothering to determine whether state and federal wetland regulations even permit what they’re planning to do.

Then there is the water. Vineyards are thirsty. A mature vineyard may manage on rainfall in a good year, but a young vineyard establishing root systems—like this one with its 400 plants and dreams of 800—requires supplemental irrigation, particularly during dry spells. This means thousands of gallons over the course of a growing season. Where is that water coming from? A well, presumably. The same aquifer that serves the neighboring properties. And what happens when you begin extracting significant volumes of water from a shared underground source? Ask any hydrologist. The answer involves words like “drawdown” and “depletion” and “impacts to neighboring wells.” But no one has asked a hydrologist, because no comprehensive environmental review has been conducted.

This is not an oversight. This seems to be a strategy. The Williamses have not provided the DEC wetland mapping—why? Perhaps because the mapping might reveal that their plans violate setback requirements. They have not conducted a proper environmental review—why? Perhaps because the review might conclude that the chemical loading, the water extraction, and the infrastructure impacts are inconsistent with residential zoning in a sensitive ecological area. They have not done the studies because, it seems, they do not want to know what the studies would say.

The traffic study is equally revealing in what it conceals. It was conducted in January when the dirt roads are frozen solid and no one ventures out on horseback because the wind off the hills will flay the skin from your face. Karen McGraw observed: “Since January is not representative of road conditions in the spring or after rains, does the Town recognize that there can be deep ruts that grab the wheels of your car, scrape the bottom of a low riding car, potholes that develop quickly in vulnerable areas and corrugated sections that develop?” A traffic study conducted in January for a venue operating May through October is not analysis. It is the paperwork equivalent of a fake Rolex—superficially plausible until you look closely and notice the second hand doesn’t sweep.

What the neighbors do know—what they have already lived through—is the noise. The sound carries. Mercer Warriner and George Lewis noted that “the noise from a recent party there carried over the hills and fields all the way to our property on Route 66, which is about 2 miles away as the crow flies.” Heather Uhlar explained the physics: “The property, owned by the Williams family, is located at the top of a large hill, overlooking the homes and farms in the valley below. When large gatherings occur at a location such as this, the sound travels down into the lower surrounding properties. It essentially creates a megaphone effect.” The Williamses have, in effect, purchased nature’s own amplification system and are proposing to rent it out for weddings.

The safety concerns are equally concrete. Norman Levine: “This neighborhood is well known as horse country. Residents and visitors often ride and fox hunt along these dirt roads. Introducing alcohol tastings and large gatherings increases the risk of accidents, including drunk or speeding drivers hitting horseback riders or pedestrians. Bashford has no sidewalks, no posted speed limit, and no centerline.” He submitted a quantitative risk analysis using Monte Carlo simulation: “The data indicates an 18% annual chance of at least one serious traffic accident if the winery proposal remains unchanged. To put this into perspective, over a typical 5-year period, there’s a 64% chance of at least one serious accident happening. Over 10 years, this likelihood rises to nearly 85%.” His comparison: “You wouldn’t board a plane with an 18% annual crash rate. You wouldn’t live in a house with an 18% yearly fire risk.” Approve this application, and you are essentially scheduling the tragedy. The only question is which year it arrives.

The legal arguments are equally devastating. One fundamental problem: the Williams property is not located in a certified agricultural district—a fact the town’s own Building Department Inspector Kent Pratt “was unaware” of when making his decision. Kathleen Tylutki of the New York State Department of Agriculture and Markets confirmed that “in order for a farm operation to be protected under Agriculture and Markets Law 305-a, they would need to be in a county, State certified agricultural district.” The Williamses are not. Their entire agricultural defense collapses on this single fact.

Even if they were in an agricultural district, the production numbers doom them: “The fact that the application states that the entire farm hopes to produce 300 bottles of wine in 2026 and 2027 dictates that it would be impossible for the operation to meet the required 70/30% revenue ratio if any weddings were held.” Three hundred bottles. To support a commercial tasting operation and event venue. This is not viticulture; it is fiction.

Martha Coultrap and Harvey Bagg dissected the timeline: “The owners represented that they produced 150 bottles of wine from their 400 plants in 2024 and will do the same in 2025. It is not clear when that wine will be drinkable. Because grapevines must be at least three years old before they are mature enough for the grapes to be harvested for wine, if, as the owners assert, an additional 400 plants are planted in 2026 and 2027, those plants will not be mature enough for wine making until 2029 and 2030 and not drinkable for at least one or more years thereafter.” One hundred fifty bottles. That is roughly twelve cases. A robust dinner party could go through that in an evening. This is not a vineyard. This is a wine-themed Instagram backdrop with agricultural pretensions.

Kate Butler drew the contrast with genuine operations like the Chatham Berry Farm and Greenhouse Cidery—“local and properly located,” “a community center, not an outsider for rent venue,” “a true extension of a preexisting legitimate agricultural business.” She concluded: “Loud, disruptive event venues have no place in residential rural areas, particularly those with dirt roads intended for low volume local traffic. Isn’t this why we have zoning?”

The Chatham Dirt Road Coalition warned: “Ultimately this whole commercial enterprise, with its parties, wine tastings, weddings etc. will set a precedent for similar enterprises on our rural dirt roads and in the process open a Pandora’s Box of acrimony and ill will in our bucolic town.” Not a single member of the community is on the record supporting the Williams’ plan.

And here we arrive at the psychology of the thing. What kind of people persist for half a decade against this wall of opposition? What does it take to face your neighbors at the Old Chatham Country Store, the Malden Bridge Post Office, knowing they have hired lawyers to stop you, knowing they have submitted actuarial analyses quantifying the likelihood of tragedy, knowing that not a single letter of support exists? Imagine the hubris—pursuing an unnecessary, ego-driven vanity project that will change a community forever, and just not caring.

Nerve. That’s what it takes.

Regina Wenzek noted: “The Williams don’t live at that house. They will be the only ones spared the noise of these parties.” I should qualify this statement. The Williamses do live there—but not in the summers. They have the Lake George pad to retreat to when the bridesmaids start their karaoke performance five wines into a dark summer night.

I know Ed. We both worked in healthcare. I was running a large medical practice that included an ENT practice—Ed is an ENT trained in facial plastics with a practice nearby. We met when he proposed that our group use the operating rooms he owns in Latham, and we declined. He gave the hard sell anyway. That’s Ed. The hard sell. The assumption that resistance is simply insufficient persuasion. At that time, he had no idea that I was a native son of Columbia County. It was my mother who had a different last name and still lived in town who “outed” me. She and Ed attended the same small church.

But I would not say we were friends—friendly professionally, sure, but we never socialized, even after I moved back to Chatham. I might see him at a cocktail party and wave, but it would end there. I thought he was a little showy (the Tara-like house again), but nice.

It was during COVID that I saw a different side of Ed. I had taken a new position at Columbia University’s Healing Communities Study, working on the opioid epidemic (my work would later be published in the New England Journal of Medicine). When COVID shut everything down, I was still working, now dealing with two deadly diseases. The misinformation was everywhere, and there was not an academic or public health professional who was not challenged by both the actual disease and the conspiracy theories swirling around it.

It started like a lot of things started in the beginning of the pandemic—on Facebook. Ed was supporting the efficacy of hydroxychloroquine in a public discussion with my neighbors, and I was shocked. I ignored it. Then after two glasses of wine and a long day of watching people die, I weighed in.*

I said that what he was saying was dangerous.

He said he was a physician. Which was my point exactly. And I am not. His point exactly.

Never mind, however, that I’m a researcher who wrote a textbook on infectious diseases, never mind that I was funded by NIH—Ed was confident he knew better. He sent a DM saying he wanted to talk to me about it, but he never called, and I know why.

Because his position on hydroxychloroquine wasn’t based in science but in his politics. Once you understand that, the story of Fox Hill Estate & Vineyard begins to make sense: the insistence on being right in the face of evidence, the belief that rules apply to other people, the conviction that what he wants is what should happen regardless of what anyone else thinks.

You see this trait a lot in medicine, especially in my experience with surgeons. And what is this trait? A profound belief that their success in one domain was a function of their superiority rather than education, circumstance, luck and the labor of others. They start to think the skills they have in the OR are applicable to any craft—farming, check; vintner, check. And then this confidence morphs into the belief that they are omnipotent.

They stop hearing no. Every denial becomes a challenge to try again with a slightly different approach, because surely the problem is not the project. How could it be?

Everything is possible. Everything can be modified. Maybe that is the nature of a plastic surgeon. Agriculture can mean parties. A dirt road can become a commercial thoroughfare. Wetlands can be ignored. Environmental reviews can be skipped. If nature or the neighbors or the Planning Board says otherwise, you just need a better pitch, a revised application, another January traffic study.

Deborah Butler identified the species precisely: “Opportunistic people on the other hand thrive on chaos and confusion. They assume small rural towns are not smart enough, have the gumption or financial resources to say no.”

It tracks—all of it. The plan, the planners, and the large middle finger to their neighbors. And it’s not just Ed. Fox Hill Estate & Vineyard is a joint project, a shared delusion. Ed, the man who makes his living convincing people they need to be improved, sees land the way he sees a nose: raw material awaiting transformation, a before picture waiting for its after. Cherie, it seems from her online life, wants to create something the Kardashians would approve of—hosting gatherings where she can pour wine for guests who will admire the view from the hilltop and compliment the stone façade and pretend that what they’re drinking isn’t twelve cases of hobby wine.

Together, they have convinced themselves that what they want is reasonable, that the neighbors are being difficult, that persistence will eventually be rewarded. That the community objects, that the concerns are not address, that the Planning Board keeps asking for documents they haven’t provided, that twenty-plus letters in the file say no—none of it registers, because the shared vision is too intoxicating to abandon. They are prepared to keep coming back, like a hydra regenerating after each defeat, until they wear everyone down. Because for Ed and Cherie, this was never about wine. It is about being seen. And the thing about people who need to be seen is that they cannot imagine why anyone would choose to look away.

I think about Guilderland, where I also spent time growing up, and what happened to it starting in the 1940s. Stuyvesant Plaza was just farmland, Western Avenue was a country road. Now the farms have given way to malls and fast-food chains, to cheesy homes with fake Palladian windows and vinyl-sided chimneys. Every place that turns into Guilderland was once a Chatham. The transformation happens one approval at a time, one “scaled back” project at a time, one exhausted Planning Board at a time. It happens when people with money and persistence wear down people with jobs and families who cannot attend every meeting, cannot write every letter, cannot hire lawyers to match the lawyers on the other side.

Norman Levine warned: “Approving this project could set a harmful precedent by encouraging more commercial event spaces on unpaved residential roads. Other vineyards in Chatham, such as Sabba and Hudson-Chatham, are situated on paved main roads with infrastructure capable of handling visitor traffic. Bashford is not appropriate for this level of commercial use.”

This project is a nose job on the land where I grew up—an unnecessary cosmetic procedure imposed on a landscape that was fine the way it was, that didn’t ask to be improved, that was beautiful precisely because no one had tried to make it beautiful. It is being proposed by someone who has made a fortune convincing people that nature’s first draft is merely a suggestion, that dissatisfaction is a business opportunity, that everything can be fixed if you just find the right specialist.

It seems not to matter that literally no one is willing to publicly support this project. It seems not to matter that so many are opposed this project. A community put out because two rich people want to cosplay at being a Napa Valley destination.

The dirt roads remain unpaved, for now. Spencer’s Field is still there, even if the Spencer’s are long gone. The wetlands filter the water and hold the floods at bay, unassessed and unprotected, waiting to see if anyone will bother to map them before the parking lot goes in, before the chemicals start flowing downhill, before the aquifer starts to drop.

And the hydra keeps growing new heads. Five years and counting. The hydra has money. The hydra has time. The hydra cares only about the hydra.

I reached out to Ed Williams. Our exchange is included below.** On the land where the vineyard is located, there are no cattle. On the parcel of land that he owns where the cattle reside, there is a sign requesting people in the event of an emergency to call Donal Collins—who is a farmer and my understanding is that Dr. Williams leases this land to him. But they are two different properties. The Fox Hill Vineyard is not farm land. It is residental.

Dr. Williams did in fact attend Cornell, but according to his own podcast (you can find it here), he did not study farming, but physiology and chemistry.

I’ve included references on wine growing and pesticides. My research does not support his position.

I do support his position on land conservancy, but not this way. There is an avenue to preserve Columbia County. The Columbia Land Conservancy has been working on this project for many years. They offer tax benefits to landowners and steward the land.

The financial benefits of “eco-tourism” are controversial. They are not always a plus. In this case it is hard to see the benefit. A wine tasting facility and the taxes it brings do not go to local municipalities - sales tax goes to the state. The benefit would be employment. More traffic means more work for the town. More work means more revenue needs to be spent.

Dr. Williams speaks to his experience in regulatory compliance. We share this skill. In healthcare - that expertise is very different than agriculute. The expertise employed in healthcare regulatory compliance is not expertise in land and agricultural regulatory law.

I admire hardworking people. Ed Williams is a hardworking man - no doubt. Getting up in the morning before school and attending to livestock is not easy. I know - I’ve done it to.

But working on a farm does not mean one is a farmer.

When I was in graduate school, studying public health, I studied and worked on “superfunds.” Nassau Lake is one. Right up the road. His postion around wetlands needs more oversight.

While the town believes that the end goal is 800 vines, in Ed’s letter to me, it is now 5,000.

There are no business endeavors on Bashford Road.

You can also review all the documents, including public comments by clicking here.

*On March 28, 2020, the FDA granted an Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) that allowed chloroquine an FDAd hydroxychloroquine from the Strategic National Stockpile to be used to treat certain hospitalized patients with COVID-19 when a clinical trial was unavailable.

However, the FDA revoked that emergency use authorization after determining that chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine are unlikely to be effective in treating COVID-19. Additionally, in light of ongoing serious cardiac adverse events and other potential serious side effects, the known and potential benefits no longer outweighed the known and potential risks. FDA

Multiple studies provide data that hydroxychloroquine does not provide a medical benefit for hospitalized patients with COVID-19. Drugs.com The World Health Organization and the U.S. National Institutes of Health have also stopped studies evaluating hydroxychloroquine for the treatment of COVID-19 due to a lack of benefit. Current NIH and US treatment guidelines do not recommend use of hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine for COVID-19 treatment.

According to the Mayo Clinic, hydroxychloroquine does not treat COVID-19 or prevent infection with the virus that causes COVID-19. Mayo Clinic

It’s worth noting that hydroxychloroquine is FDA-approved to treat or prevent malaria, and to treat autoimmune conditions such as lupus and rheumatoid arthritis. FDA has determined that these drugs are safe and effective when used for these diseases in accordance with their FDA-approved labeling. FDA The revocation only applied to the COVID-19 use.

**Dear Ed,

I am currently preparing an article for Substack and NewsBreak regarding your and Cheri’s proposed winery and tasting room project, as well as the community response it has generated. In the interest of balanced journalism, I would like to offer you the opportunity to share your perspective on this matter. Should you wish to respond to the following questions, I will ensure your comments are included in the article.

What is your long-term vision for this project? Do you anticipate expanding the vineyard operations? If so, does your business plan include projected crop yield increases for years three through five?

What are your projections for visitor traffic to the vineyard and tasting room over the same timeframe?

When will the town and neighboring residents receive detailed specifications not currently included in the application, such as building dimensions and parking capacity?

When will a DEC environmental assessment report regarding the designated wetlands be made available?

Public records indicate plans to use portable sanitation facilities. Could you provide details on the maintenance schedule for these units, particularly as it relates to service vehicle traffic?

My research indicates that northeastern grape cultivation typically requires chemical intervention to prevent endemic fungal issues. Specifically, compounds such as Mancozeb, Captan, Azoxystrobin, Tebuconazole, and Imidacloprid are widely considered essential by eastern grape growers. Will you be utilizing these or similar pesticides?

Have you explored organic cultivation methods as an alternative?

What are your plans for irrigation?

How do you respond to the concerns expressed by community members who oppose this project?

What measures, if any, are you considering to address concerns regarding noise and increased traffic?

I welcome the opportunity to discuss these matters by phone, or you may respond via email at your convenience.

Sincerely,

Josh Powell

(518)### ####

And the response:

Good morning Joshua,

I’m not sure which email you had on file, but this is my current and preferred address. I wanted to take a moment to answer a few of the questions regarding our vineyard, and also provide some context for those who do not know Cherie and me personally.

Although our winery project is relatively new, we are certainly not new to this area or to agriculture. I grew up in a rural farming community and worked on a dairy farm for over ten years through college and medical school. As an undergraduate I attended and graduated from the Agricultural & Life Sciences School at Cornell, so farming has always been in my blood. Cherrie and I moved to this area almost 30 years ago, raised our four children here, and have been actively involved in the community—our church, the Old Chatham Hunt Club, and various local efforts.

In recent years, as I’ve had a bit more time, we decided to pursue additional agricultural endeavors. We’ve had beef cattle on our property for about 15 years, and we are now expanding into viticulture. We currently have 400 grapevines planted, with a long-term vision of growing to approximately 5,000 vines. Our goal is to produce a premium New York State wine and support the agricultural community, especially given the development pressures we are all witnessing in the area. Preserving farmland is important to us, and this project allows us to contribute meaningfully to that mission.

Our site is an ideal east-facing slope with Manlius-Channery soils, and we’ve done extensive research in collaboration with Cornell Cooperative Extension to ensure correct placement of crops and grape varieties suited to our microclimate here in Columbia County. While much of this is informed by data and agricultural science, some of it will naturally involve experimentation—common to all new vineyards in the Northeast.

With regard to compliance, this is an area I am extremely familiar with. I have founded, managed, and operated a fully accredited ambulatory surgery center and surgical practice more than 30 years, so compliance—state, federal, and regulatory—is something I navigate every single day. In comparison, agricultural and farm-winery regulations are very straightforward. We have engaged Crawford Engineering out of Hudson, along with legal counsel, to ensure we meet all requirements, including traffic and noise studies.

A few of the other concerns raised—such as irrigation or wetlands—are not particularly relevant for our site. Irrigation is generally unnecessary after the first year in the Northeast because our soils retain adequate moisture, unlike California vineyards. Our vineyard location is well outside any wetlands, situated on high ground, so that is a non-issue.

From a practical standpoint, I do not anticipate that a small farm winery and tasting room will create anywhere near the road impact compared to the daily FedEx, delivery trucks and heavy equipment that already service numerous businesses along our road. New York State is actively promoting agricultural development—including vineyards—in Long Island, the Finger Lakes, and right here in the Hudson Valley. Columbia County is part of that broader initiative to strengthen tourism and agriculture.

I’m not entirely sure why this has become controversial, as we are simply exercising our rights as long-standing farmers with deep roots in Columbia County. Our intention is to preserve open land, contribute to the local agricultural economy, and create something of quality that reflects well on the community.

I hope this helps clarify our goals and answer your questions.

Warm regards,

Ed

References

Carmichael, S. L., Yang, W., Roberts, E., Kegley, S. E., Padula, A. M., English, P. B., Lammer, E. J., & Shaw, G. M. (2014). Residential agricultural pesticide exposures and risk of selected congenital heart defects among offspring in the San Joaquin Valley of California. Environmental Research, 135, 133–138.

Cornell University. (2024, August 23). EPA considers delisting mancozeb for use in grape. National Grape Research Alliance. https://graperesearch.org/2024/08/23/epa-considers-delisting-mancozeb-for-use-in-grape/

Gold, K. (2025, May 16). Update on mancozeb use in grapes. Purdue University Facts for Fancy Fruit. https://fff.hort.purdue.edu/article/update-on-mancozeb-use-in-grapes/

Luo, T., Wang, Y., Zhang, Y., Li, X., Chen, L., & Liu, X. (2023). Neonicotinoids in the environment: A review of their distribution, transport, ecotoxicity, and human health impacts. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 30(15), 42898–42917.

Martín-García, A., García-Cela, E., & Fernández-Cruz, M. L. (2024). Pesticides and winemaking: A comprehensive review of conventional and emerging approaches. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety, 23(5), e13419. https://doi.org/10.1111/1541-4337.13419

Michigan State University Extension. (n.d.). Late-season fungicide sprays in grapes and potential effects on fermentation. https://www.canr.msu.edu/news/late_season_fungicide_sprays_in_grapes_and_potential_effects_on_fermentatio

Minnesota Department of Agriculture. (n.d.). Mancozeb fungicide. https://www.mda.state.mn.us/mancozeb-fungicide

Minnesota Department of Health. (n.d.). Imidacloprid and groundwater. https://www.health.state.mn.us/communities/environment/risk/docs/guidance/gw/imidainfo.pdf

Penn State Extension. (2024). Overview of EPA proposed cancellation of mancozeb in grape production. https://extension.psu.edu/overview-of-epa-proposed-cancellation-of-mancozeb-in-grape-production

Pires, S. M., Magalhães, M. J., & Oliveira, M. B. P. P. (2021). Systemic effects of the pesticide mancozeb: A literature review. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva, 26(6), 2231–2238. https://doi.org/10.1590/1413-81232021266.34162020

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. (2005, September). Reregistration eligibility decision (RED) fact sheet for mancozeb (Case No. 0643). https://www3.epa.gov/pesticides/chem_search/reg_actions/reregistration/fs_PC-014504_1-Sep-05.pdf

Virginia Cooperative Extension. (n.d.). Fungicide spray guidelines for non-bearing vineyards (Publication SPES-315). Virginia Tech. https://www.pubs.ext.vt.edu/content/dam/pubs_ext_vt_edu/spes/SPES-315/SPES-315.pdf

Wikipedia contributors. (2025, October 26). Imidacloprid. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Imidacloprid

Xiong, J., Wang, L., Xu, Q., Wang, Y., & Zhang, L. (2023). Neonicotinoid insecticides in drinking water: Occurrence, fate, and health risk assessment. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 458, 131876.

Zhang, Y., Li, M., Wang, X., & Chen, H. (2024). Imidacloprid affects human cells through mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress. Science of the Total Environment, 951, 175572. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.175572

This is the reality of our society. The ongoing deterioration and destruction of Democracy. It’s bullshit! A plastic surgeon! Vanity at work! So, how many followers do you have? We would require email addresses, cell phone numbers, website addresses etc. And a coordinated effort, and agreement, from the majority. We overwhelm those communication systems and networks. 24 hours a day, 7 days a week! Not verbal abuse or threats. Just democracy at work. An expression of disagreement, by the vast majority! I’m retired, active, but I’m confident I can find the time to participate!