The War of Rosé: When Bucolic Dreams Become Bacchanalian Nightmares

A Follow-Up on Fox Hill Estate and Vineyard

This is a follow-up to last week’s article on “Fox Hill Estate and Vineyard.”

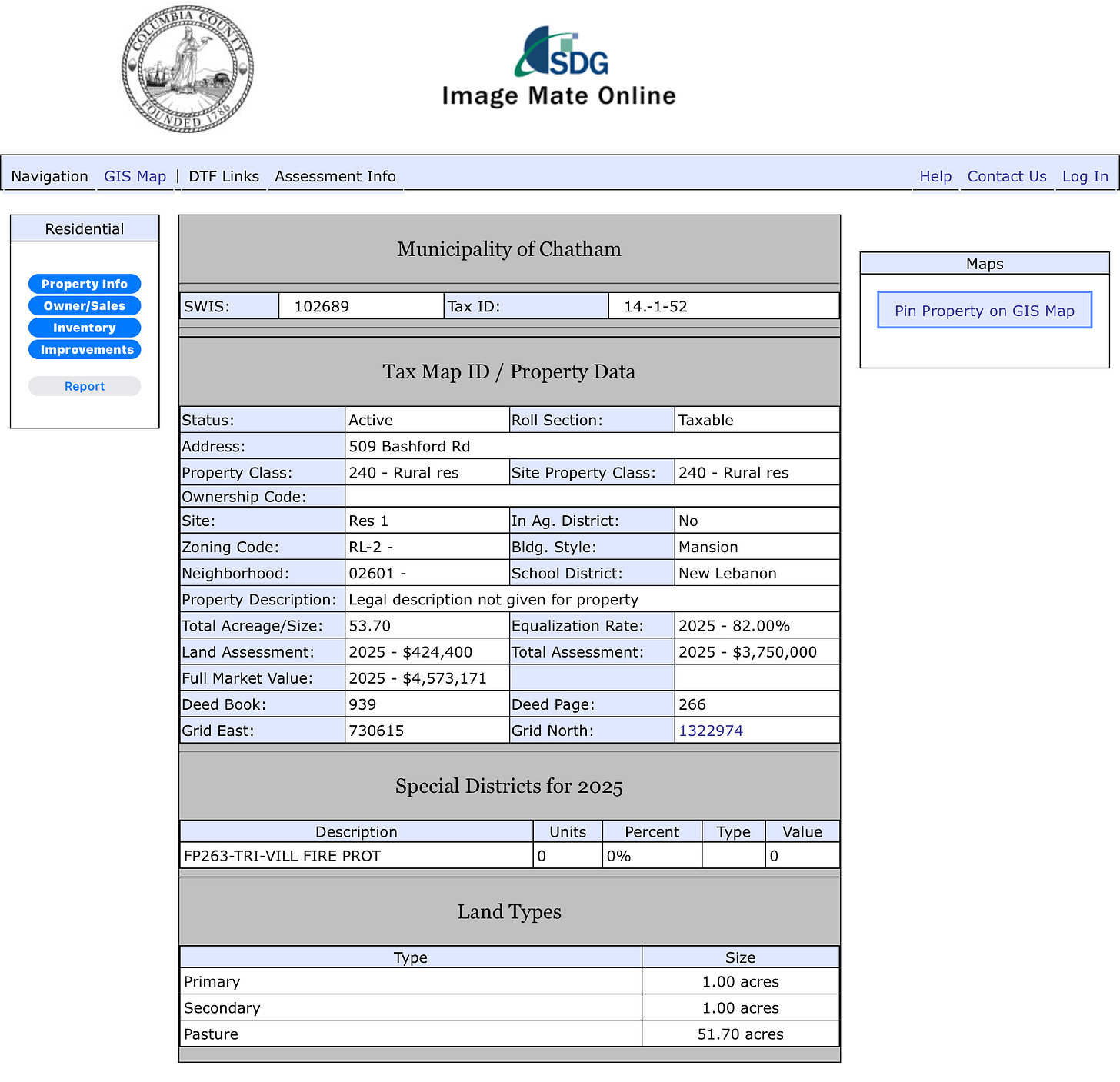

I attended Thursday night’s zoning board of appeals meeting. There was no decision whether the Williams will be able to open their tasting room. Why? Because there was a lot of confusion as to the property’s zoning. Specifically, if the property is in a designated “agricultural district” it would make it easier for the project to move forward as there would be protection under the NYS Agricultural laws. No one was able to put their finger on the zoning - the irony - it was the Zoning Board of Appeals.

Well, it is not in a designated agricultural zone (see below).

So the decision, which is a matter of law, was oddly punted to a public hearing. So now’s the time to speak up and ask some real questions and revisit questions that have not been answered.

Starting January 1st, 2026, most of my work moves behind a subscriber paywall.

Right now, you can lock in a year for $35—or $5/month. After January 1st, the annual rate rises to $50.

Should a private home in a mixed-used residential zone be allowed to side-step requirements? Should a “tasting room” for wine be allowed to charge patrons for admission for what is akin to a bar without a liquor license?

It was openly discussed last night that there is actually no wine currently being produced. Which makes one wonder - why the need for a “tasting room”? Why not just have people over for a glass of wine?

If Fox Hill Vineyard can open a tasting room - selling wine that is not part of the actual farming endeavor - what’s next? Moreover, what exactly is a garage selling alcohol without a liquor license? Maybe it’s just a speakeasy.

Everyone should ask themselves if this is allowed - just where does it end, because this could change everything. It will set a precedent. A burger joint on a patio. An Amazon drop off spot in a driveway. It is a slippery slope.

So maybe sometimes, just sometimes, the past is not only something to remember, but also instructive.

When I was a boy, my mother worked in Albany. She taught school in Arbor Hill for her entire career as an educator—her choice, really. My mother possessed that increasingly rare quality: a sense of social justice that wasn’t just lip service. Being a woman in the 1960s working in what they politely called ‘the ghetto’ was not easy, but she was beloved by the children and parents in what was for all intents and purposes a segregated corner of Albany.

Her refuge, her safe harbor, was our house on Richmond Road. On weekends and school vacations she would toss us kids outside feeling safe in the knowledge we’d not get hit by cars or end up on the back of milk cartons. It gave her a break from kids at work and us at home. Importantly, it gave us a profound love of nature and independence.

My mother loathed driving, so my father—a portrait painter who worked from home in that enviable way artists sometimes managed before “working from home” became code for checking email in sweatpants—would bundle my younger sister and me into the car to collect her after her school day. We always took the same route home: down Route 66, then a right turn onto Richmond Road. It was a long, lovely stretch between 66 and our house. Only two other residences interrupted the pastoral rhythm: Mrs. Heller’s house, an old colonial set back from the dirt road, and a trailer, for the resident farmhand, tucked away to the right before the intersection of Reed and Richmond roads.

Then came our house, and across the street, the barns where the Spencers raised Haflinger ponies—those sturdy, golden creatures that looked like they’d wandered out of a Brueghel painting. I was four when I witnessed my first foal being born. Good Friday 1969. My father and Mr. Spencer were in the stall, sleeves rolled up, helping to pull the young creature into the world. The vet, Dr. Zweig, pronounced it a miracle that the foal survived. They named it Friday, naturally. Because when you’re delivered on Good Friday against long odds, subtlety seems beside the point.

Between our house and the Spencers’ place on the corner of Richmond and Bashford roads, there were no other homes. The Selbys built theirs—now the Alberts’—in the 1980s.

The Spencers, in the early 1980s, then well into their golden years, sold their home—horses gone, that chapter closed—and built something new that’s now Sue Tanner’s. The Williams’ house hadn’t been constructed yet. The rest of Bashford held families like the Valentinis, who kept an African Grey parrot named Coco. Mrs. Valentini owned the Warm Ewe yarn shop on Chatham’s Main Street, tucked adjacent to The Main Street Bookstore, the Handicrafters, and Brown’s Shoes—the latter three owned by the Marks, the Blocks, and the Rosens respectively, that particular constellation of Jewish merchants giving Main Street whatever cultural pluralism and sophistication it possessed.

It was an idyllic start to life, the kind of childhood that now seems as remote as daguerreotypes. Some readers are undoubtedly wondering if my opposition to the Williams’ wine vineyard and tasting room is nothing more than the protest of a man with a pen and a reflexive hostility to change.

I’m not opposed to change. I’m opposed to the kind that destroys community fabric for the sake of someone’s boozy business fantasy. The kind that turns dirt roads designed for horses and slow-moving cars into commercial thoroughfares. The kind that mistakes agricultural cosplay for actual farming.

All people really need to do is examine what has already happened in this community—object lessons in what happens when ambition collides with inadequate oversight, when people and towns fail to ask the hard questions before the damage becomes permanent.

The Pond That Died of Neglect

Consider the large brick house on the square in Old Chatham. When Mr. Quinn sold it, the woman who bought it suffered from that peculiarly American delusion that enthusiasm can substitute for competent stewardship. The dam—her responsibility—fell into disrepair, a gradual collapse of infrastructure that happened in plain sight. But it was her property…people took the hand’s off approach.

That pond was every local kid’s winter rec center. While parents would meet at Jackson’s —drinking and dining in the style of 1970s leisure — we children claimed the ice as our kingdom. Mr. Mickle, who owned the big house across from the pond—Albert Callan’s old place—installed a floodlight for us. It had a switch we could operate ourselves, a small gesture of trust that seems unthinkable in our current age of liability panic and helicopter parenting. After snowstorms, we’d descend like a swarm, the sound of skates scraping and shovels pushing snow off ice creating that particular music of childhood—the metallic scritch-scratch punctuated by laughter and hockey sticks slapping pucks.

On that pond, Ilana Marks and I trained for the Olympics. Never mind that I wore hockey skates and our routine consisted entirely of holding hands, skating fast in circles and gliding far into the now long-lost, frozen canal. We were never headed for gold. The dream was sufficient unto itself.

Today’s children won’t have those memories because the pond is gone—choked by cattails and milfoil, those botanical markers of neglect made visible. The water that once froze smooth as glass in January now sits stagnant and diminished, a monument to what happens when owners view property as asset rather than trust.

Subsequent owners tried their hand at Airbnb—the neighbors objected with the ferocity you’d expect when strangers start showing up on your square with rolling suitcases and Airbnb attitudes. They poured money into the house. The pond got nothing. Dr. Ira Marks—the GOAT of the OC, a man who actually understood what community meant—tried to orchestrate restoration before he died. He failed. It still hasn’t been done. It won’t be. People don’t know what it was.

And then there was the architectural vandalism on the house itself. One need only look. Someone built what can only be described as a hospital wing onto the historic house—an addition so grotesque, so fundamentally wrong, that if buildings could develop cancer, this would be classified as a Stage IV malignancy.

I cannot imagine the Petersons who lived in the large white house across the street looking across the square at that horror show every morning. Though perhaps after a few years, horror becomes wallpaper. You stop seeing it because seeing it would require acknowledging that you live in a community that had no way of stopping it. No one likes powerlessness.

Had there been a historical preservation commission—with the power to say “no” and make it stick—Old Chatham would look entirely different today. But there wasn’t, and Old Chatham lost a treasure.

The Old Chatham Sheepherding Company

Perhaps a more relevant comparison exists on Shaker Museum Road. Few lived there when I was growing up: Lisa and Peter Cox, the Mayers, Anita Drown, Wiggie Williams, a few others and the Jurings on the corner of Shaker Museum Road and Route 13. As children, we’d bicycle down to what we called Drown’s swimming hole. Pony Club held their shows there. And of course, there was the Shaker Museum, that repository of American austerity and craft, reminding us that people once built furniture to last centuries rather than until the IKEA warranty expired.

Nancy and Tom Clark bought Wiggie’s house and transformed it into the Old Chatham Sheepherding Company. They installed a creamery and built substantial barns for their flock.

It was genuinely lovely—a serious agricultural operation that employed local people, contributed to the tax base, and somehow managed to be both commercially successful and aesthetically appropriate to its setting.

Some at first objected to the Inn, of course. There are always objectors. But the entire enterprise made sense within the landscape. It enhanced rather than violated. It added rather than subtracted.

The Clarks eventually sold their house on Route 13—the old Cutler place— closed the Inn, and moved in full-time. They maintained the creamery, kept it contributing. Tom kept the farm operational for years, the land hosting the now-defunct Old Chatham Horse Trials, back when horses still mattered more than Escalades.

Time, that merciless accountant, is never kind. The Clarks aged—as we all do, if we’re lucky—and decided to sell what some still called Wiggie’s, others the Sheepherding Company, and many simply the Clark’s.

They didn’t get anywhere near their asking price. Some said the interior required demolition of the bar built for the Inn. The sprawling old house and outbuildings demanded constant attention and deep pockets. And then there was the sheep operation itself—they’d spared no expense, built it properly, done it right. But try finding actual shepherds in 21st-century America. Try finding people willing to work with livestock for wages that would make a barista laugh. What had seemed like a sound investment—to many of us, myself included—became that most American of tragedies: the white elephant. The thing that made perfect sense until it suddenly didn’t, until the market decided it wanted something else entirely.

Eventually it sold. The new owners, Silver Brothers Distillery, bought it. The barns were converted and they too are planning on opening a tasting room. Their plans on this tasting room are vague in some respects. It is a work in progress. What is not vague? Their detailed site plan and environmental impact study. They did their work. You can read it here.

Their farming is real and their monthly newsletter is up to date and provides a concrete document and forum to inform the community and, importantly, hear from them.

They repurposed the barns and disclose things like community employment. It is clearly a business with benefits to the community and transparency. It is also using the farmland as farmland. They are using an existing infrastructure. Their plans for a tasting room will carry the potential for risk. All tasting facilities do. Fact.

No report can mitigate the public safety issues that operations like these have the potential to bring to communities. This is not to say it can’t be done right.

But behind every carefully curated Instagram aesthetic—the golden-hour photos of wine glasses against vineyard sunsets, the rustic chic of repurposed barn wood, the whole performative authenticity of it all—lies a history of alarming public safety failures in this industry—and it should be discussed openly.

This is not conjecture. This is not NIMBYism dressed up as concern. This is what the data actually shows when you bother to look.

Napa and Sonoma counties have the highest DUI arrest rates in California’s Bay Area, with 95% of first-time offenders serving jail time—21% above the state average.

A “designated driver” who’d been wine tasting in Geyserville killed two passengers.

A limousine leaving Long Island’s Vineyard 48 made a U-turn and was broadsided, killing four young women. The other driver was convicted of drunk driving. For years there were accidents on this stretch of highway - it could not accommodate the increase traffic associated with Vineyard 48.

In Indiana, a woman who left a Sazerac Distillery work party visibly intoxicated drove the wrong way on an interstate and killed two women and a child.

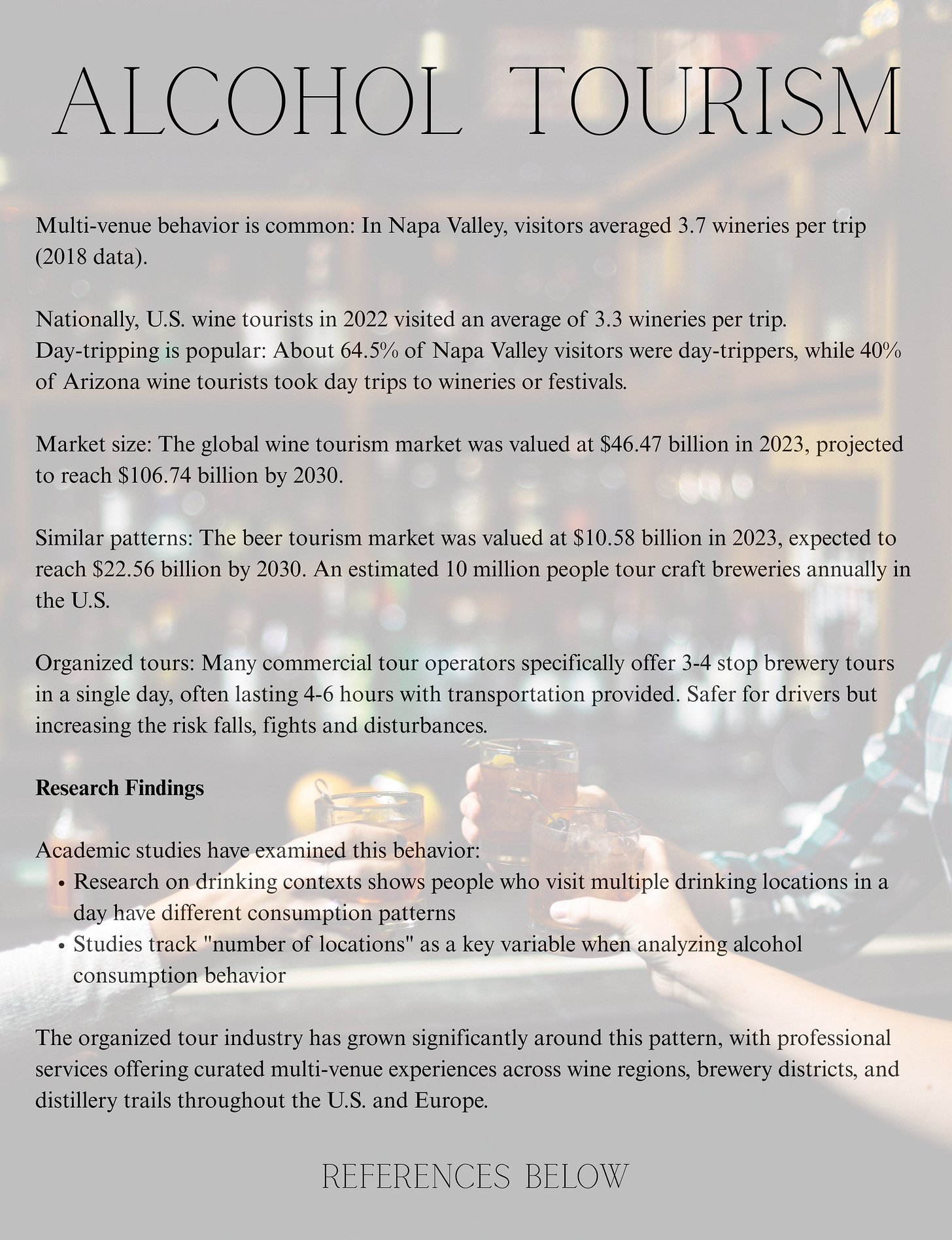

Wine tastings typically involve six samples of 1-3 ounces each—up to 9 ounces total, nearly two standard drinks at one location.

Visits to multiple tasting venues compound the effect as the data shows. Another tasting venue only brings more risk. And while some are on more “friendly” roads like Harvest Spirit’ on Rt 9 nearby, it is not just roads that poses risk. It is not unusual for people to go on tasting room field trips visiting multiple venues on the same day.

The 2015 Silver Trail Distillery explosion in Kentucky killed distiller Kyle Rogers and critically injured another worker. Investigation found the still wasn’t designed to hold pressure but was equipped with a relief valve rated at 150 psi when manufacturer specifications stated it “operates on less than one pound of pressure.” Since the 1990s, major distillery fires have destroyed facilities at Heaven Hill (90,000 barrels, $30 million in losses), Wild Turkey, Jim Beam twice, with warehouse collapses at Barton 1792 (120,000 gallons spilled) and O.Z. Tyler. The Wild Turkey fire killed hundreds of thousands of fish along 66 miles of the Kentucky River.

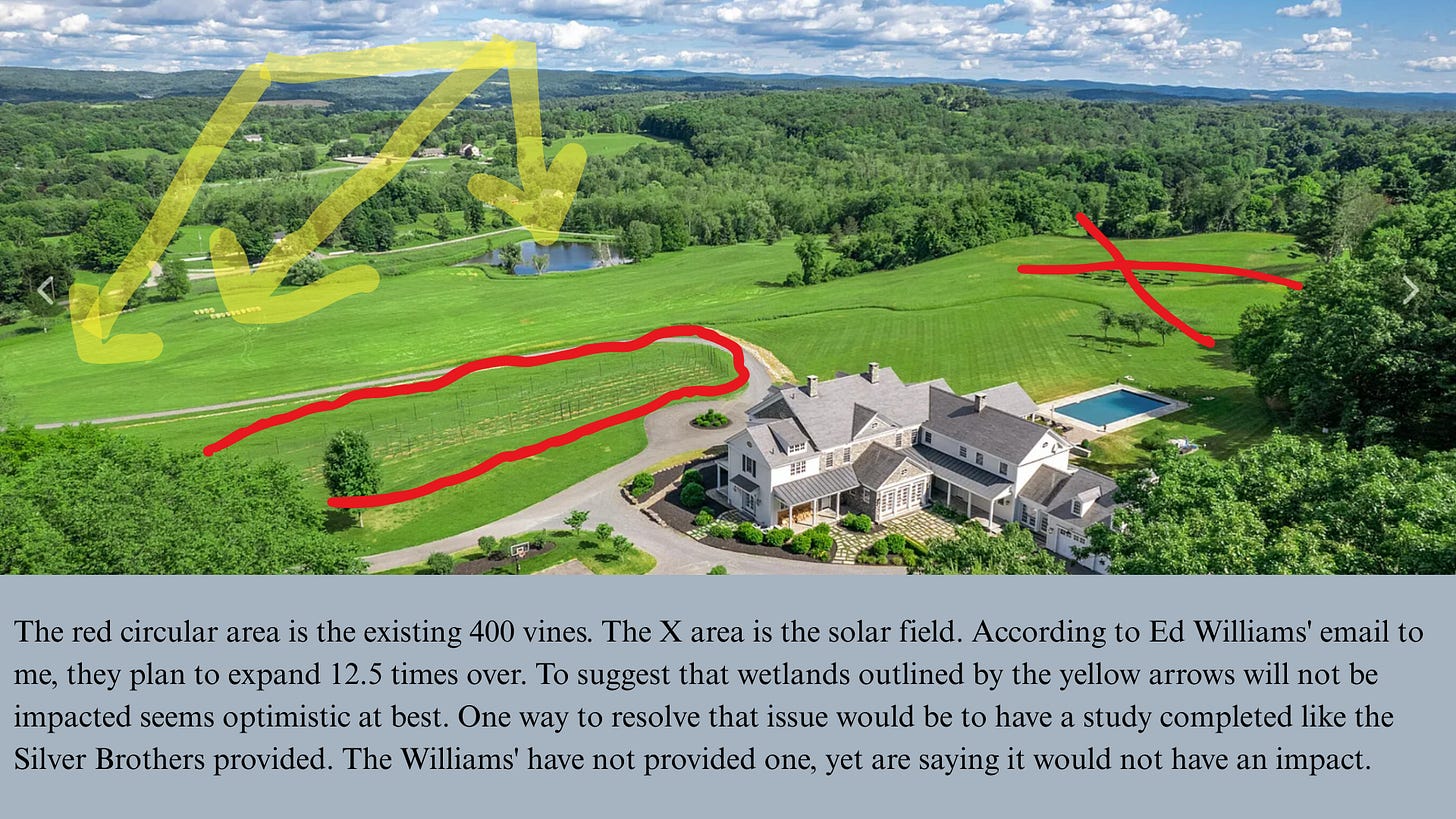

The dangers are not abstract, pollution threats are real - just look at Nassau Lake. Review the study that the Silver Brothers provided to the town on water concerns to both the agricultural need and the potential threat to the Kinderhook Creek. They paid for and made public documents that provide a plan that Silver Brothers will not be a Wild Turkey or a Nassau Lake.

The explosive growth of wine tourism has overwhelmed rural communities never designed for such traffic—communities built for tractors and horse trailers, not tour buses and bachelorette party vans. The winery scene on Long Island’s North Fork exploded to 43 producers from a handful in the 1970s, straining roads, emergency services, and police resources past their breaking point in communities where the tax base can’t possibly support the infrastructure demands.

One venue, Vineyard 48, shut its doors amid an emergency suspension of its liquor license in October 2017, after it became “a focal point of police attention,” according to court documents.

Police were forced to dedicate two or three officers every weekend simply to monitor this single venue. That’s a grotesque diversion of law enforcement resources that rural communities can ill afford.

The local farmers out on Cutchogue - actual farmers, complained that tasting rooms created traffic congestion that made moving equipment between fields dangerous, parking nightmares that block access roads during harvest, and sewage issues harmful to genuine agricultural operations and salmon habitat when “temporary” facilities became permanent and overwhelmed.

These aren’t mere inconveniences. They represent fundamental conflicts between agricultural preservation and commercial entertainment venues masquerading as farms. The industry has successfully lobbied for “farm” designations providing favorable zoning and tax treatment while operating what are transparently bars and event venues—having their cake, eating it too, and leaving the mess for someone else to clean up while they retreat to their other houses for the summer, age out or go belly up (think SABA Wine in Chatham).

The industry’s response to mounting safety concerns more often has been performative rather than substantive—theater designed to forestall actual regulation while maintaining the appearance of responsible stewardship.

Concerns over legal liability for intoxicated guests have encouraged most wineries to ostentatiously limit the number and size of pours—posted policies promising “responsible service” that look impressive in their liability insurance applications. Yet an Inside Edition investigation captured footage of staff pouring generous helpings for “tastings” at Vineyard 48, revealing how easily these limits evaporate when profit beckons, when the tip jar is looking light, when the bachelorette party wants “just a little more” and threatens a bad Yelp review if you don’t comply.

Trade associations have created safety programs serving primarily as public relations exercises rather than meaningful reform. Approximately 17,500 people from production breweries have completed the Brewers Association’s online brewing safety course since 2014—impressive-sounding numbers that look great in press releases. Yet brewery injuries increased from 160 in 2011 to 530 in 2014 during this exact period of supposed safety enhancement.

Voluntary training programs prove insufficient when workplace safety culture remains fundamentally broken, when the incentive structure rewards corner-cutting and punishes caution, when the guy who takes time for proper safety procedures is the guy who doesn’t hit production targets and doesn’t get promoted.

Changing the face of a community produces repercussions that ripple outward for decades—consequences that become visible only after approvals have been granted, infrastructure installed, precedents established.

The owners of “The Brick House” in Old Chatham harbored business ambitions—the pond and the community anchor it represented to multiple generations simply didn’t factor into their calculations. They saw an asset to be maximized, not a trust to be preserved. The pond died of neglect while they focused on Airbnb revenue projections. Now it’s gone, and with it, the winter memories an entire generation might have had.

The Old Chatham Sheepherding Company was genuinely inspired—a serious agricultural operation that respected its context while contributing meaningfully to the local economy. But changes to the property cratered its value when the market shifted, when the Clarks aged out, when finding shepherds in 21st-century America proved impossible. But the Clarks stuck it out until their property sold. This is not always the case. All one has to do is take a ride down to the end of Southerland Road where the old Ooms farm died and was abandoned—the house and barn in tatters—trailers rusting—garbage tossed out of cars as if it was a dump.

Like the Clarks, Ed and Cheri Williams won’t live forever—nobody does, though all of us act as though mortality is negotiable. What happens to Fox Hill Estate & Vineyard when they’re gone? Does it become another white elephant? It is a relevant question. And yet another uncomfortable truth worth confronting: Ed and Cheri listed their property for sale three years ago. What really is their commitment?

One way of gauging commitment would be conducting EPA studies. Sharing relevant farming experience. Not misleading people with an academic history at Cornell’s College of Agriculture and Life Sciences when your studies had nothing to do with farming. It means bringing in experts who specialize in agriculture regulation—not claiming that healthcare regulatory compliance is the same thing. It means not calling yourself a farmer when the cattle on an adjacent piece of land you own are not even yours. And it means listening to and addressing all the people who oppose this project and acknowledging that no one is on the public record supporting it.

Ignoring community concerns, obfuscation—be it irrelevant studies or claims—and attacking the messenger might be a strategy.

I don’t think it will work.

Actually, it’s unnecessary when right down the road there’s a template on how to do it right.

Some didn’t want that distillary, and that’s okay. The town made an informed decision because they had good data provided to them by Silver Brothers.

This might be a good starting point for Fox Hill Vineyards. Silver Brothers’ application submitted years ago is online. It’s a great template.

But there remains that pesky zoning issue and a lot of unanswered questions.

Part One: The Grapes of Wrath

References

Brewers Association. (2016, February 16). Travelocity debuts new beer tourism index. https://brewersassociation.org/communicating-craft/travelocity-debuts-new-beer-tourism-index

Daley, E. (2017, January 24). Beer tourism boom brews up across the US, showing no signs of slowing. BeverageDaily. https://www.beveragedaily.com/Article/2017/01/24/Beer-Tourism-boom-brews-up-across-the-US-showing-no-signs-of-slowing

Grand View Research. (2024). Beer tourism market size, share & growth report, 2030. https://www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/beer-tourism-market-report

Grand View Research. (2024). Wine tourism market size, share & trends report, 2030. https://www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/wine-tourism-market-report

Hotelagio. (2024). Wine tourism statistics: Trends and insights for 2025. https://hotelagio.com/wine-tourism-statistics/

Shore Craft Beer. (2021). Craft beer tourism research study. https://shorecraftbeer.com/craft-beer-tourism-research-study/

Terry-McElrath, Y. M., Patrick, M. E., Evans-Polce, R. J., & Schulenberg, J. E. (2023). Alcohol use contexts (social settings, drinking games/specials, and locations) as predictors of high-intensity drinking on a given day among U.S. young adults. Alcohol: Clinical and Experimental Research, 47(2), 273-284. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10084771/

Tourism, Arizona Office of. (2024, June 25). Arizona wine tourism study reveals over 500% growth since 2011. https://tourism.az.gov/arizona-wine-tourism-study-reveals-over-500-growth-since-2011/

Vinetur. (2024, October 22). The rise of wine tourism in the U.S. https://www.vinetur.com/en/2024102282482/the-rise-of-wine-tourism-in-the-us.html

Copyright © 2025 Joshua Powell/The Powell House Press. All Rights Reserved.

This work is protected by copyright law. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, transmitted, displayed, performed, or used in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the copyright owner, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other noncommercial uses permitted by copyright law.

Unauthorized copying, reproduction, distribution, public display, public performance, or other unauthorized use of this copyrighted material is strictly prohibited and may result in severe civil and criminal penalties. Violators will be prosecuted to the maximum extent permitted by law.

For permission requests, contact josh@thepowellhousepress.com

Fantastic piece on infrastructure mismatch. The comparison between Silver Brothers' detailed site plan and Fox Hill's lack of documentation really gets at something critical about rural development most people miss. I've seen similar tensions in Vermont where a "farm" tasting room suddenly needs three officres on weekends just to manage traffic, but nobody factored emergency services into approvals. The slippery slope argument around precedent setting isnt just rhetorical either.