How To Get Away With Murder: A Columbia County Fix

War Heroes, Union College, Old Money, and a Death on Route 9H: How a Small-Town Network of Power Covered Up a Killing.

This story once had a blast radius. Today, all of the people involved are dead. This is the true story of just how things can happen in Columbia County, New York, because they did. It is more than just a story of small-town justice or the lack thereof. It is about corruption even though well intentioned. And the players involved, well-known names, were not looking for tax breaks or personal profits.

To understand how a woman was killed and the man responsible was charged with manslaughter, but walked free and mentioned only once in a buried blurb in the Register Star, you have to understand what war did to men and the loyalty it bred. You have to understand men who shared a visceral love for their Alma Mater, Union College. And more importantly, you have to know how Columbia County, New York works. When you understand all of this, a back-room zoning deal is like a game of pick-up sticks by comparison.

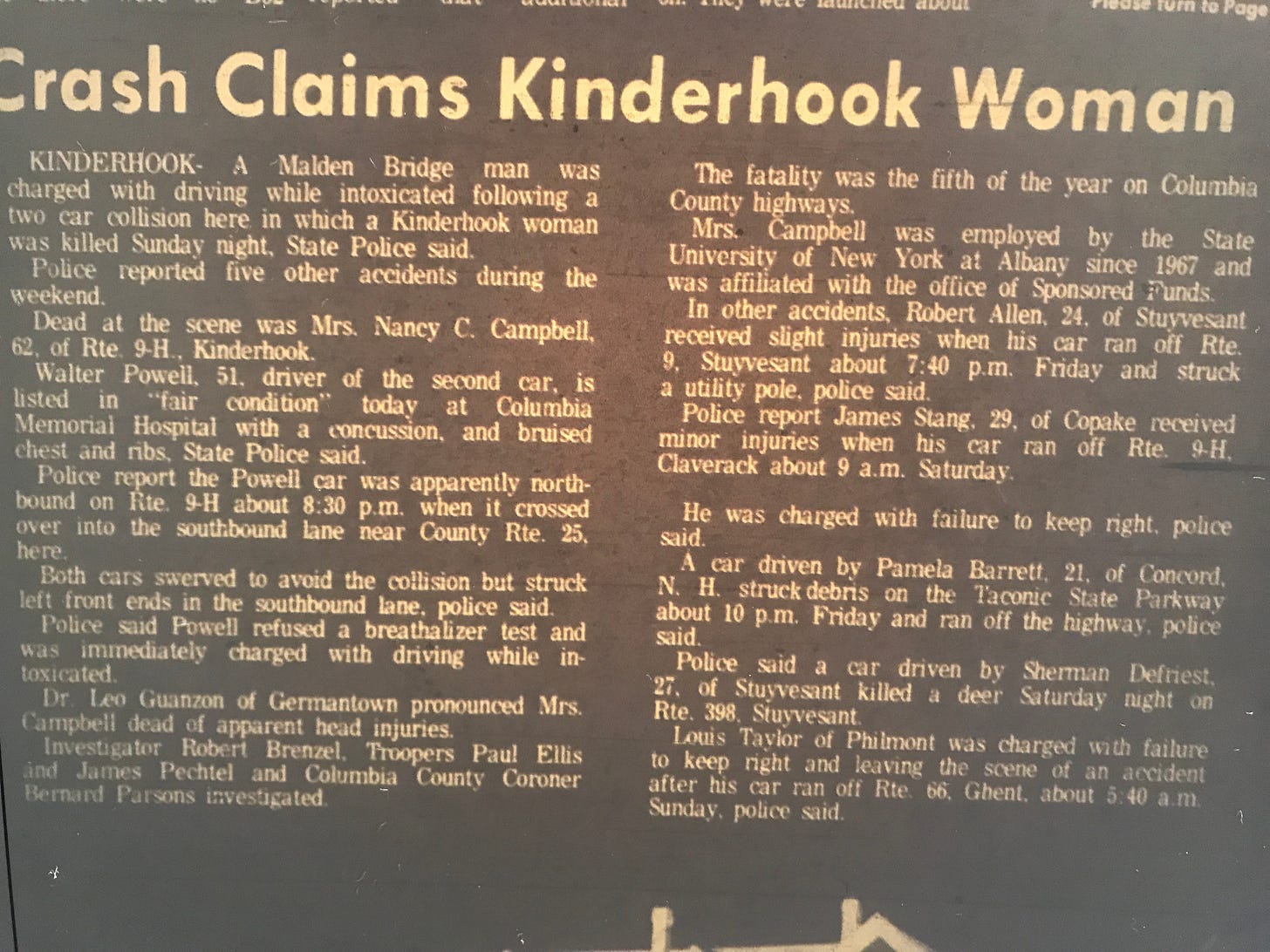

On a dark stretch of Route 9H in March of 1972, a woman was killed when she was struck head on by a drunk driver. Her death was instant and violent. Her body was crushed and she was almost decapitated. She had gone out to get a pack of cigarettes and was a mile from her home.

Her name was Nancy Campbell. She and her husband Kenneth owned Lindenwald, the historic home of President Martin Van Buren in Kinderhook, New York, which today is a National Historic Site.

The man who killed her was my father. He was a decorated World War II veteran who had left the University of Michigan to join the Canadian Black Watch as a sniper before the United States had even entered the war. When he came home, he resumed his studies at Union College.

The crime was covered up by two men: Albert Callan Jr., the publisher of the Chatham Courier, and Burns Barford, a power broker in his own right. Together, they orchestrated an elaborate effort to ensure my father was never prosecuted and that the victim’s widower was quietly compensated, ultimately through the sale of Lindenwald to the National Park Service.

Burns Barford, a family friend, came from a very prominent Columbia County family. His father, Burns F. Barford Sr., had been the Columbia County District Attorney and later served as assistant attorney general of the State of New York. His grandfather, James Purcell, had been an elected county clerk of Columbia County. Burns himself was a lifetime resident of Valatie who attended Union College, graduating in 1937, and then Albany Law School, where he graduated cum laude in 1940. Like Albert, Burns was a veteran. He served in the China Burma India Theater for two years, holding every rank from private to major. After the war, he set up a law practice in the Village of Valatie. In 1955, he was appointed Surrogate Court Judge of Columbia County, though he was no longer on the bench at the time my father killed Nancy Campbell. He also served as a director and chairman of the board of the National Union Bank of Kinderhook and for many years as attorney to municipalities across the county. He was a man who knew everyone and wielded quiet but considerable influence.

Albert Callan Jr. was one of the true princes of Columbia County, a man whose life read like the résumé of three or four different men. His father, Albert S. Callan Sr., had purchased the Chatham Courier back in 1912 and built it into an influential regional weekly. When the elder Callan died in 1963, Albert Jr. assumed the role of publisher, but he had been running the paper as editor for years.

Before the war, Albert had studied French and German at Union College in Schenectady, graduating with the Class of 1941. He enlisted in the U.S. Army just before Pearl Harbor and was assigned to military intelligence, eventually serving on the staff of General George S. Patton. In late 1944, operating alone as an intelligence officer, he was sent on a spy mission into the small village of La Croix Sur Meuse to determine the extent of the German military presence there. He identified several tanks and called in American soldiers to liberate the town. Years after Albert’s death, a plaque was unveiled in La Croix celebrating him as its “Liberator.”

When Albert came home and took over the Courier, he didn’t settle into the quiet rhythms of small-town journalism. Just a few miles south of Chatham, the city of Hudson harbored one of the most brazen vice operations in the northeastern United States. Hudson’s Diamond Street had been the center of a world of prostitution, gambling, and government corruption, all operating under the protection of local law enforcement and elected officials. Through his reporting, Albert helped expose it, and his work contributed to a dramatic reckoning: in 1950, Governor Thomas E. Dewey ordered a surprise raid on Hudson by New York State Troopers. The arrests netted not only the operators of the brothels and gambling parlors but also the mayor and the chief of police. For this work, Albert was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize, an extraordinary distinction for the editor of a small-town weekly.

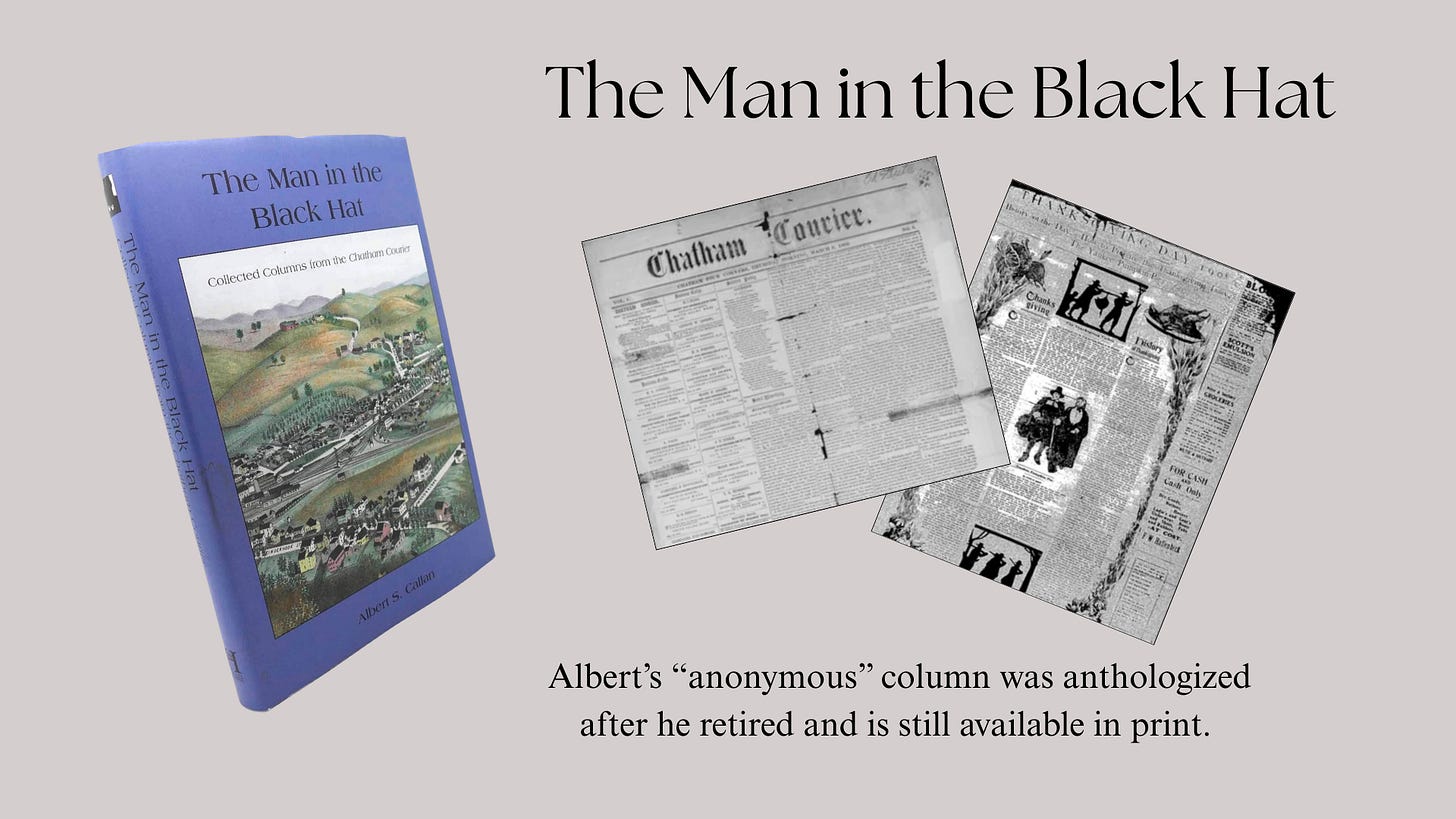

Albert also wrote a weekly column called “The Man in the Black Hat” that ran in the Courier from 1946 until shortly before his death in 2005, a span of nearly sixty years. Though the column was officially unsigned, its authorship was, as one account noted, the worst-kept secret in Chatham and surrounding towns. According to his Union College classmate Larry Schwartz, Albert was recognized by the Guinness Book of World Records as the longest-living columnist in history.

All three men had served in the war. All three had attended Union. That was the bond, and they remained very close friends until my father died in 1976.

Between Albert’s control of the press and Burns’s legal connections, they had the means to make the whole thing disappear. And they did.

Before Lindenwald became a monument to American democracy, it belonged to Nancy and Kenneth Campbell, a couple who had cashed out of car dealerships in Putnam County and bought the place with visions of grandeur. The Campbells didn’t appreciate what they had. The place looked very different when they owned it, nothing like the Italianate residence we know today. They had tried, and succeeded to some degree, in remaking the historic home into something more suited to their taste. The entire community was horrified. Sounds familiar, doesn’t it?

Nancy commissioned a portico on the front of the house that destroyed the façade, a cosmetic insult that scandalized preservation-minded locals. Their approach to repackaging a historic part of Columbia County did not sit well. 509 Bashford was not the first pillared home to raise eyebrows.

Maybe most notable among those bothered by what the Campbells had done to the property was Albert himself. He had long admired Lindenwald and its place in American history, and the portico was, to him, an affront. But his frustration with the Campbells would eventually intersect with a far darker obligation.

It was 2010. My brother Seth was having a birthday party for his son Finn at his place in East Chatham. The party was held outside, both young and old. Seth and Susie had set up coolers of beer and soda. There was a barbecue caterer grilling all sorts of food, and Seth was setting up his equipment for his band to start playing.

I went into the house to use the bathroom, and when I came back downstairs, I saw Ginny Callan, Albert’s widow, in the kitchen pouring herself a glass of wine. She looked awful. I went over to her, and she gave me a hug and, in her deep voice, started to chat about how things were going. She said she might go to Mexico this year but wasn’t sure, then asked about me.

Albert was Seth’s godfather and while Ginny was not Seth’s true Godmother, that honor was given to “Cousin Dot.” Yes, before Downton Abbey’s “Cousin Isobel, Dame Maggie Smith’s constant companion and foil, we had “Cousin Dot.” She had lived in Danbury but moved to Montana. As Cousin Dot’s presence faded over the years Ginny took up mantle of Godmother and we went along with it.

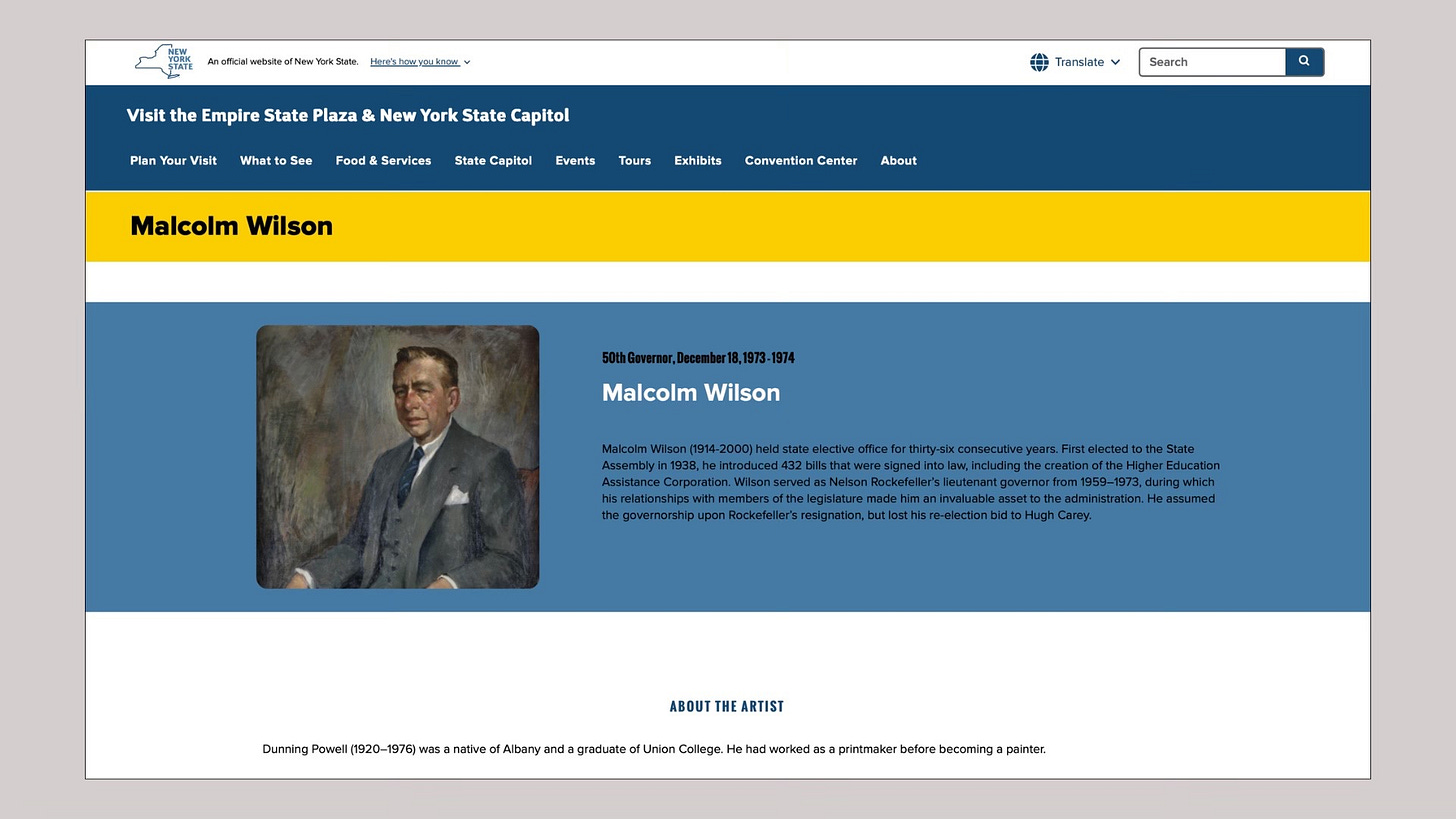

Ginny was a formidable woman in her own right. Born Virginia Cairns in Albany in 1936, she had led successful careers in radio, television, politics, and public relations. She had worked for WTRY radio and WAST television, and at WGY-WRGB in Schenectady she produced and appeared in the award-winning children’s show “Ginny’s Game Room.” An early advocate for women’s equal pay, she had been appointed to the women’s unit of the New York State Executive Chamber by Governor Nelson Rockefeller and served on a number of state and national political campaigns. Governor Malcolm Wilson appointed her as the Wilson family spokesperson. Governor Hugh Carey appointed her to direct the I Love New York campaign for the 1980 Winter Olympic Games in Lake Placid. She later opened her own public relations firm, Communications Ink, and served as a founder and president of the Women’s Press Club of New York State. She was also president of the Friends of Olana and sat on the board of directors for Columbia Memorial Hospital in Hudson, the very hospital that would figure into this story.

That day of the party the sun was starting to set, and my brother grabbed me.

“Josh, you’ve got to drive Ginny home. I’ve had a couple, I can’t. There’s no way she can drive home.”

I looked across the patio, and it was clear she was buzzed. It was as if Seth and I had cast a magic spell because all at once she got up and came over.

“This was a fabulous party, Seth, but it’s time I head home,” she said in her husky voice.

“Why don’t you let Josh drive you home,” Seth suggested.

“Yeah, Ginny, let me take you home,” I repeated.

“Don’t be silly, I can easily drive myself home,” she insisted and walked into the kitchen.

“Go get her,” Seth told me, and I followed her into the house.

“Ginny, please let me take you home,” I said, almost begging.

“Oh, don’t be silly, I’m fine. I wanted to talk to you anyway.” She hooked her arm in mine and led me out the front door. I helped her down the steps, and once we were on solid ground, she leaned on me less.

“Do you remember when you came over for lunch a few years ago?” She stopped and looked straight at me.

“Of course,” I said, remembering when I had approached Albert to tell me more about my father for a book I was planning to write about him*.

“Well,” she said dramatically, “Albert and I had some words about it. We both know what you wanted to know, but you have to understand that Albert didn’t want to get caught up in it. Certainly not after all these years and at his age.” She said it as if I understood.

I said nothing.

“He never regretted helping your father, never. But God forbid what they did ever got out! Can you imagine?” I had no idea what she was talking about. I had gone to them about another matter concerning my father.

We were at the car by now, and she was digging in her pocketbook for her keys.

“Please, Ginny, let me drive you home,” I begged.

“Don’t be silly, I’ve driven home with a few more in me than this,” she said, acknowledging her drinking.

“I want you to know that it was not murder. Yes, that woman died, but it was an accident, and your father felt awful. If you still want to talk about it, I’ll tell you the whole story. Albert’s dead now,” she said wistfully. “Besides, I think you should know the real story, but I understand if you don’t want to dredge it up.”

She turned the key and the engine came to life. She put the car in drive and took off down the road toward New Concord. Like all of the drinkers in Old Chatham, they knew the paths to take to avoid the Troopers; the local sheriff would look the other way. It was always that way.

I stood in the road and watched her taillights fade into the distance as her words started to sink in. Another death? I decided I would call her. Maybe she was just drunk and delusional, or maybe she was drunk and telling the truth.

I called her a week later. She answered on the first ring, her voice lilting with an almost musical quality.

“Hello,” she sang into the phone.

“Hi Ginny, it’s Josh. I wanted to follow up on our conversation at Seth’s the other night.” A hint of uncertainty crept into my voice. I wasn’t entirely sure she’d remember.

A pregnant pause hung between us before she spoke. “Why don’t you come down for lunch this weekend,” she said decisively. “I’ll tell you everything I know. How does Saturday around 1 sound?”

“Sounds good. See you then.”

“Bye bye,” she chirped, and the line went dead.

When Saturday arrived, I prepared carefully. I showered, shaved, and dressed with unexpected deliberation, a pressed shirt over clean jeans. Something about Ginny’s invitation felt weighted with significance. Not that she was cold or formal. It was only a few years before she flagged me down at the annual “tag sale” fundraiser for the Shaker Museum where she was volunteering. She took a few items that someone had donated for sale, put them in a bag before I could see them and asked me for ten dollars and winked at me. She was fun like this when we were kids. She knew all sorts of tricks. But this was no gag. On the ride home with my friend Peg she opened the bag. There was a small caviar dish with a small spoon from Cartier and a three-piece Christofle silver set – salt, pepper, and mustard pot.

She and Albert had sold their house in Malden Bridge and had moved to Kinderhook Lake, where they had downsized. They spent their winters in Mexico after Albert sold the Currier. Their little house, meticulously rehabbed, sat at the end of a secluded road. From the driveway, you’d never know a home nestled here; it was as if the house had been carefully tucked into the landscape, its only view was the lake. It didn’t look like the Kinderhook lake I knew as a child and was forbidden to swim in because it was so polluted. Of course it would be lovely.

Ginny opened the door before my knuckles could touch the wood, greeting me with a kiss on the cheek. Like all of “grown ups” now, time had reshaped her. Once tall and commanding, she was now slightly stooped, her frame diminishing. Her face had softened, grown puffy, betraying the quiet toll of her drinking. It seemed as if she had aged in just a fews after Seth’s party.

The table was set for a proper lunch. If you knew Albert and Ginny, well, you’d know that they had the kind of taste that would humble Martha Stewart.

“This place is beautiful,” I said, taking in the view.

“You’ve been here before, haven’t you?” she asked.

“No, this is my first time.”

A mischievous glint sparked in her eyes. “Well, let’s not make it your last,” she called from the kitchen. “Why don’t you do the honors and open the wine?”

A sterling Tiffany’s corkscrew lay on the table, a relic from another time. I remembered asking about its origin decades ago, and Ginny’s patient explanation about the famous New York City store.

She emerged with a tray bearing two steaming soup bowls and a large salad, shaking a bit as she approached the table, a sign of her need for a drink.

“Let me help,” I offered.

“Absolutely not,” she declared. “You’re the guest of honor.”

I poured our wine, and we settled into our chairs with a shared ritual of anticipation.

“Cheers!” she proclaimed, and we sipped in unison.

Her gaze drifted to the lake, softening with nostalgia. “I miss Albert,” she murmured, “especially when I see people like you, those who remember our old days.”

“It must be hard,” I responded, sensing the weight of her loss.

“Well, one must carry on!” The familiar dramatic flair underscored her words, a performance of resilience.

Then, abruptly, she shifted. “So, you came to ask about the accident. Albert was shocked when you started inquiring about your father’s past. We both understood, but he was blindsided. He thought they’d all been so... discreet.” She paused, watching the lake’s subtle movements. “Everyone felt bad for Nancy Campbell.”

Confusion swept through me. “Who is Nancy Campbell?” The question escaped me, genuine bewilderment coloring my voice.

Ginny reached for the wine bottle, filling her glass nearly to the brim, a telling gesture.

“This is awkward, isn’t it?” she said dryly.

“Is it?”

A sardonic smile played across her lips. “Well, it has the potential to become quite awkward.” She took a slug of wine. “You don’t know what happened in Ghent, do you?”

“I don’t think I do.”

She leaned forward, elbow on the table, glass in hand. “Well,” she said, her tone dry. She refilled my glass. “You might need this.”

“Ginny, I’m a grown man,” I reminded her.

“Yes, you are,” she agreed, pushing the glass on the table towards me.

“Well, where to start,” she said, her mind in a quandary. “You’ve heard of Lindenwald?”

I have her a look. Does anyone not know who grew up there?

“Hmmm... well, before it was a national park it was owned by a couple. The Campbells.”

Ginny told me everything. She told me how Dad had been driving home from the train station in Hudson that night. He’d been in New York and had a few drinks on the train, then stopped at a liquor store in Hudson on his way home. He was drinking as he drove up Route 9H. It took hours to get her lifeless body out of the car.

Dad had broken his femur, ankle, and some ribs. He was not unconscious. When the police removed him from the car, he smelled of alcohol and was slurring his words. He refused to take a breathalyzer and was immediately charged with driving while intoxicated.

It was Albert who called Burns, Ginny told me. Together, they made sure that Dad’s car would not be impounded but stayed on the side of the road so that Bill Clerk, one of “the Bills” — a gay couple who were very close family friends and lived across the road from where Jim and Lucinda Buckley live now in Malden Bridge — could retrieve the liquor bottle from the car. This part I know to be true because in all the chaos, with Mom having to get to the hospital, the Bills had come to the house to watch us until my grandmother could get to us. Bill Clerk took my sister and me with him. I remember it. I remember seeing the car and the red paper poppy the church handed out tied to the rear-view mirror. But the gravity of the situation, that was something you don’t tell a seven-year-old. What I was told was that Dad was injured after hitting a deer on the road.

“Why did the police leave evidence in Dad’s car?” I asked Ginny.

Ginny just looked at me and raised her eyebrows calling me out of my naïvety. After all, I was not a young man and had already learned so much about my family and the power of influence and how to cover-ups certain uncomfortable truths.

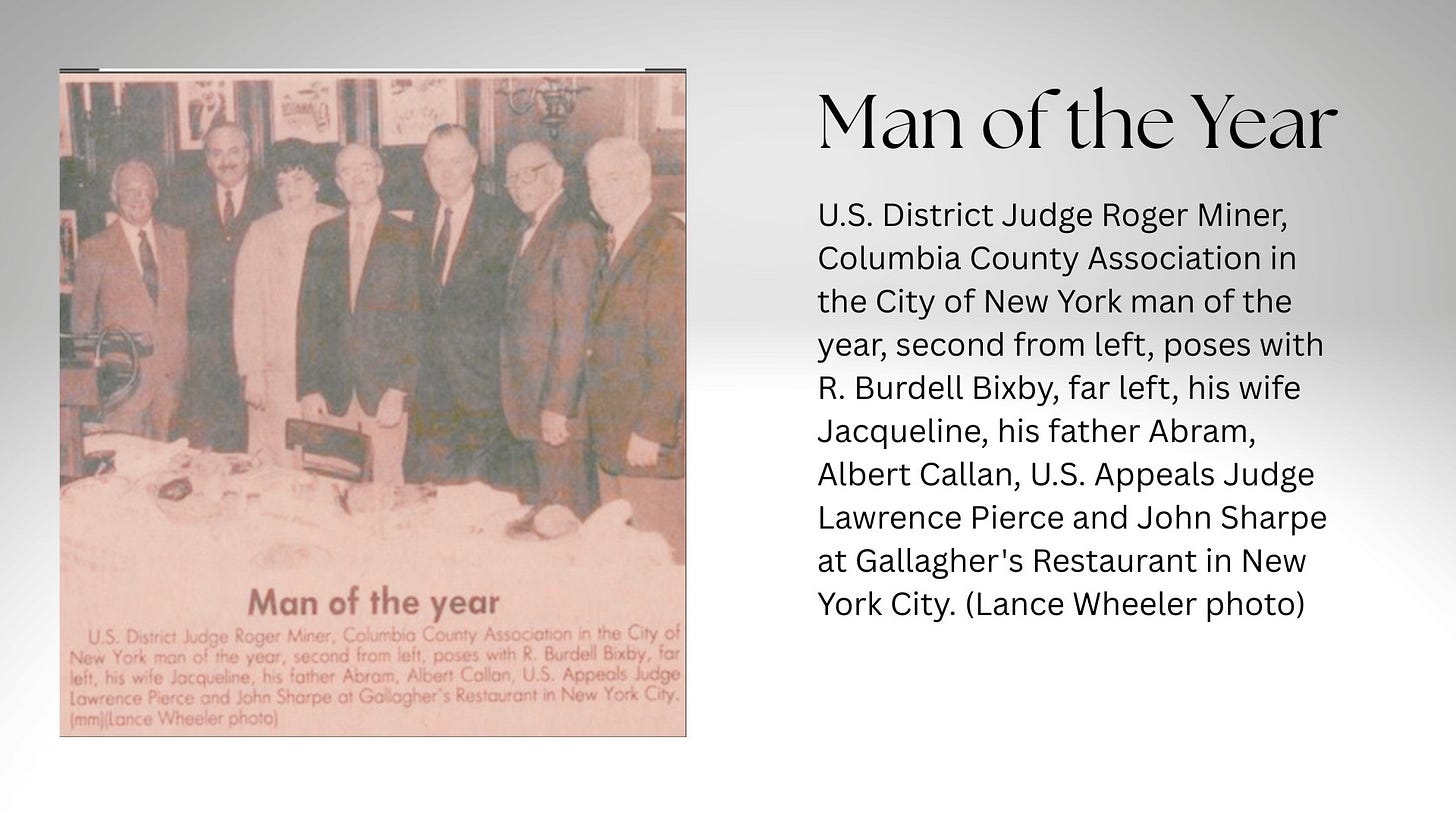

The district attorney at the time was Roger J. Miner. Miner was ambitious and the son of yet another Columbia County’s power brokers. He would later become a Federal Court of Appeals senior judge and was on the short list for George H. W. Bush’s consideration as a member of the United States Supreme Court. He was a longtime Republican, as was his father. He knew Albert well, as did his father. Albert was a leading figure in upstate Republican politics, having served as a committeeman of both the Columbia County and National Republican Committees.

“Roger had a lot of ambition,” Ginny continued. “He achieved a lot. Wanted a lot more. He was not onboard with what Albert and Burns were pitching. Can you imagine the fallout of letting a man with your father’s past go free?”

That was why Dad stayed in the hospital as long as he did and was not transferred to Albany Medical Center for his surgery days after the accident. Columbia Memorial Hospital was a safe harbor. Albany Medical Center was not. Ginny knew this firsthand. She would eventually sit on the board of directors for Columbia Memorial.

“The fear that Roger had was twofold,” Ginny went on. “While Albert made sure that the story was not covered in the Courier, of course that was easy since he owned it, he also made sure that the Times Union and Knickerbocker didn’t run any story on it. But the Register Star... they were a pain in the arse. They ran a small blurb about it but were convinced not to cover it further.”

The irony was thick enough to choke on. Here was Albert Callan, the man who had made his journalistic bones exposing political corruption in the county, who had been nominated for a Pulitzer for his fearless reporting on the vice operations in Hudson, whose work had helped bring down a mayor and a chief of police, now using the very same influence and connections to bury a story. The man who had shone a light on Diamond Street was casting a shadow over Route 9H.

“How were they convinced?” I asked. It all seemed too fantastic to be true.

“Fighting the powers that be could have its consequences, I suppose.” Ginny got up and went back into the kitchen. I heard the refrigerator door open, and she returned with another bottle of wine and handed it to me to uncork. I filled her glass and poured a half glass for myself.

“The other consideration was Ken Campbell. If he were to raise a stink, who knew where things would go. Roger needed assurances,” she said, raising her glass and eyebrows at the same time.

She continued. “A couple of things were happening at that time. One was that Albert, myself, and a few others had made Olana a historic site and museum.”

“I remember that,” I said. “I remember going there with Dad and Albert letting us go anywhere.”

Ginny smiled. This was the time when she and Albert had started dating and became “Albert and Ginny.”

“Olana set a template of sorts for the acquisition of historic homes and turning them into museums and parks. For years, people had wanted to do the same with Lindenwald, but the Campbells wouldn’t sell. They had some money after selling their car dealerships, but then they caused a small scandal when Nancy had that portico built. It totally ruined the look of the place,” Ginny said, sounding almost like she was sneering. “In any event, they had no idea how much it would cost them and they started to run out of money.”

She excused herself and went to the powder room. I got up, stretched my legs, and looked around at the beautiful things they had collected. My mind was swimming with questions, but Ginny told a story in her own time, and I knew most of them would be answered if I was patient.

She came back and topped off her wine. When she went to give me more, I said I had to drive and had better not. She gave an eye roll as if to say I was a party pooper.

“Where was I?”

“You were telling me the Campbells were running out of money. How did you know that?”

“There were signs. He started an antiques shop in one of the outbuildings, but what he really sold was junk. She took a state job. And of course Burns knew because they asked the (Kinderhood) Bank for a loan. Burns was the Director of the Bank. There was some leverage.”

I rocked back in my chair. The idea that these men would go to such lengths for my father and had the confidence to do so was mind-blowing.

“After Olana, Albert knew how to pull off making a historic home into a park. Honestly, he had wanted to take over Lindenwald ever since the portico was built.” Ginny stopped to take a breath and eat a bit of her salad.

What Ginny was saying sounds far fetched, but there’s documentation.

The historian Suzanne Julin, writing years later in her administrative history of the park for the National Park Service, would identify Albert as the single most important figure in the preservation effort. Julin noted that while Edward Welles III had organized much of the formal preservation push, Welles was a polarizing figure. But Julin was clear about who mattered most: Albert Callan Jr. had followed in his father’s footsteps as an influential citizen vitally interested in county history, and he strongly supported the preservation of Lindenwald through news stories, editorials, and personal efforts. He would go on to become the founding chairman of the Friends of Lindenwald in 1984 and later mount a successful editorial campaign against a proposed landfill near the historic site. What Julin could not have known, or at least never put into print, was that Albert’s passion for Lindenwald was entangled with a darker thread.

“Ken needed money, and the park offered him five times what he paid for Lindenwald. They also allowed him to stay on the property for life in the gatehouse!” Ginny exclaimed. “He was supposed to pay rent, but that was rubbed out. The park only asked him to pay his light bill in the shop.”

The details, as I would later learn from Julin’s publication, were even more specific. The purchase agreement for the 12.86-acre estate was for a total price of $102,000. To put that in perspective, if invested in the S&P 500 back then, it would be worth around $34 million today. Campbell, who was seventy-eight, was allowed to continue living in the house for three years with an option for a fourth year. The National Park Service finalized its purchase from the National Park Foundation on August 20, 1975.

“God,” I said, taking another sip of wine.

“Oh, it was something to pull off. And Albert and Burns made sure Ken was always taken care of.”

“How so?”

“In every way. It got to the point where the maintenance staff were asked to check on him when he got older. They also checked in with him on any changes that were going to be made, so he was not shocked or upset too much. It was over the top.”

Over the top was an understatement. What had been intended as a temporary humanitarian arrangement became a years-long administrative headache. Warren Hill, who oversaw the early management of the site from his post at the Franklin D. Roosevelt and Vanderbilt Mansion National Historic Sites in Hyde Park, cautioned his staff in no uncertain terms: paramount in all responsibilities was assuring a continuing good relationship with Mr. Kenneth Campbell. Staff were to review with him each day the work they expected to accomplish so that he was fully knowledgeable and was not surprised by anything done in and around the estate.

Campbell’s original three-year lease was extended repeatedly, first by a year, then by a fifteen-day emergency extension, and then through a series of special-use permits after he moved into the South Gatehouse. An “accessory use” if you will. A tasting room without the crowd.

Superintendent Bruce Stewart justified the extensions by citing Campbell’s advanced age, fragile state of emotional and physical health, and lack of close relatives. Meanwhile, Campbell’s presence created practical problems beyond mere administrative inconvenience. He had shut off all but four rooms to renovations, he had installed extension cords throughout the building, and when staff inspected, they found the cords had worn through in many areas in the basement, with several 110-volt lines hanging from ceilings.

“Wow” was all I could manage to get out.

“It really worked out for everyone. Ken was taken care of for life and had a nice nest egg. Albert and Burns were thrilled to have Lindenwald turned into a historic site. And your father stayed out of prison.”

I sat for a moment and looked at Ginny with a certain awe and horror. How transactional they made Nancy Campbell’s death. How they orchestrated the freedom of my father. How federal money was used to pay off Ken Campbell.

“Ginny, I don’t get it. Why did Albert and Burns do this for Dad?”

“They were all in the war. They all went to Union. You might not agree with it, but that is what friends did for each other. Besides, how would your father going to prison of helped?” She asked. She was not looking for an answer.

After coffee, I said I had to go.

“Well, I guess that was a lunch you didn’t expect,” Ginny laughed in her husky way.

“No, it was not,” I said, giving her a kiss on the cheek.

Driving home, I felt like I was floating. It seemed almost impossible that my father had killed a person and faced a homicide charge right under my nose, while I was alive, while I was a child in his house. But I knew it was true. It cleared up so many oddities that had made no sense.

When my friend Ellenor Cox (Pete and Lisa’s daughter who grew up on Shaker Muesum Road) had once claimed to remember Dad being involved in the death of someone, it was not a false memory. In March of 1972, the accident that Dad supposedly had because he almost hit a deer was a lie. He had hit a woman. The reason we went with Bill early that morning to the scene of the crash was not to get things out of Dad’s car. It was to collect bottles of liquor. Known evidence.

I eventually found the small article in the Register Star. Dad did, in fact, kill Mrs. Campbell. He was charged and never prosecuted. I also found the publication commissioned by the National Park Service, Suzanne Julin’s administrative history of Lindenwald, which confirmed everything Ginny had told me. Campbell’s health began deteriorating rapidly in 1979, and he was hospitalized repeatedly over the next year, but he did not want to move away from the gatehouse. Despite concerns about his well-being, the special-use permit was extended one final time. Late in 1980, his relatives were appealed to about the elderly man’s living situation. By the end of the year, Campbell had been relocated to a nursing home. Kenneth Campbell died on January 2, 1981. Even in death, his presence lingered. His personal possessions and the antiques from his business filled both the South Gatehouse and the shed he had built on the property until May 1981, when they were finally removed and the shed demolished. What the official record called compassion, I now understood as something more complicated: a debt being honored, a silence being purchased, a deal being kept. And of course, corruption.

It was not long after I had lunch with Ginny that Mom called me.

“Ginny died,” she said flatly into the phone. So many of Mom’s friends were dying or dead. “They found her on the floor. She’d been there for a few days. I can’t imagine.”

Virginia Cairns Callan died on November 28, 2008, at the age of seventy-two, at her residence in Niverville, New York. She had been Albert’s wife for thirty-five years.

Albert himself had died on December 2, 2005, at the age of eighty-seven. He is buried at Spencertown Cemetery in Columbia County. The plaque in La Croix Sur Meuse calls him a liberator. The Guinness Book of World Records called him the longest-living columnist. The National Park Service historian who studied Lindenwald called him the most important figure in saving a president’s home. A Pulitzer nomination recognized his courage in exposing corruption. For nearly sixty years, every week, the people of Chatham and Columbia County opened their newspaper and found a familiar voice waiting for them, wry, warm, principled, and unfailingly present. The man in the black hat never really took it off. But there was a story he never told, a column he never wrote.

With Ginny’s death, one of the last living witnesses to the fix went silent. The other person who knew was my mother. She never discussed it. The deal—war buddies protecting one of their own, a woman’s death turned into a real estate transaction, federal money buying a widower’s silence, a historic landmark born from the ashes of a cover-up—would have died with her, had Ginny not sat down with me that afternoon at Kinderhook Lake and, over soup and too much wine, told me everything.

This story, some might say, is too old to be relevant. It’s not. I have newer arrows in my quiver about Columbia County and how things can get fixed. I’m not going there now; it’s not necessary.

While this may read like a tale of priviledged men, it’s more a story of a community that has a strong tolerance for backroom deals. That’s culture. One that remains long past a voting cycle or the deaths of some individuals.

All hail Columbia County, its remarkable character, history and, yes, its corruption.

And that brings us back to 509 Bashford Road. Should one man get to change the face of a community? Should a town supervisor be able to no-show a vital decision-making meeting representing the very constituents he represents? Should his relationship be disclosed?

The real question is whether this story is just history or is it a reveal of Columbia County’s political DNA?

History lesson over.

Next week: what does research at Cornell Cooperative Extension really show about commercial vineyards in New York? Spoiler alert: not what Dr. Williams claimed in his December email to me. And following this, why would the County Board of Supervisors recommend no environmental study? Not for nothing, by law, this change in zoning triggered the SEQR. But the law as this story tells is rather flexible in New York’s upper Hudson Valley.

As promised here are links to the two email updates I sent out after last week’s article.

A Dog Under the Pool Cover, a Missing Fence, and a Very Quiet Donal Collins

Yesterday was “Friday the 13th” — I don’t know, for me, it felt damn lucky.

All the information in this article was done in preperation for a book about my father. This is a modified version of two completed chapters.

Why Your Subscription Matters

Independent journalism answers to readers—not advertisers, corporations, or access-hungry editors. No story gets killed because it upsets a sponsor. No punch gets pulled because someone important made a phone call.

Your support makes possible sharp commentary, fearless satire, and reporting that follows the story wherever it leads. In an era of manufactured narratives and algorithmic blandness, that independence isn’t a luxury—it’s a necessity.

Subscribe to The Powell House Press. Or settle for content that tells you what someone else wants you to hear.

©2025 The Powell House Press | josh@thepowellhousepress.com