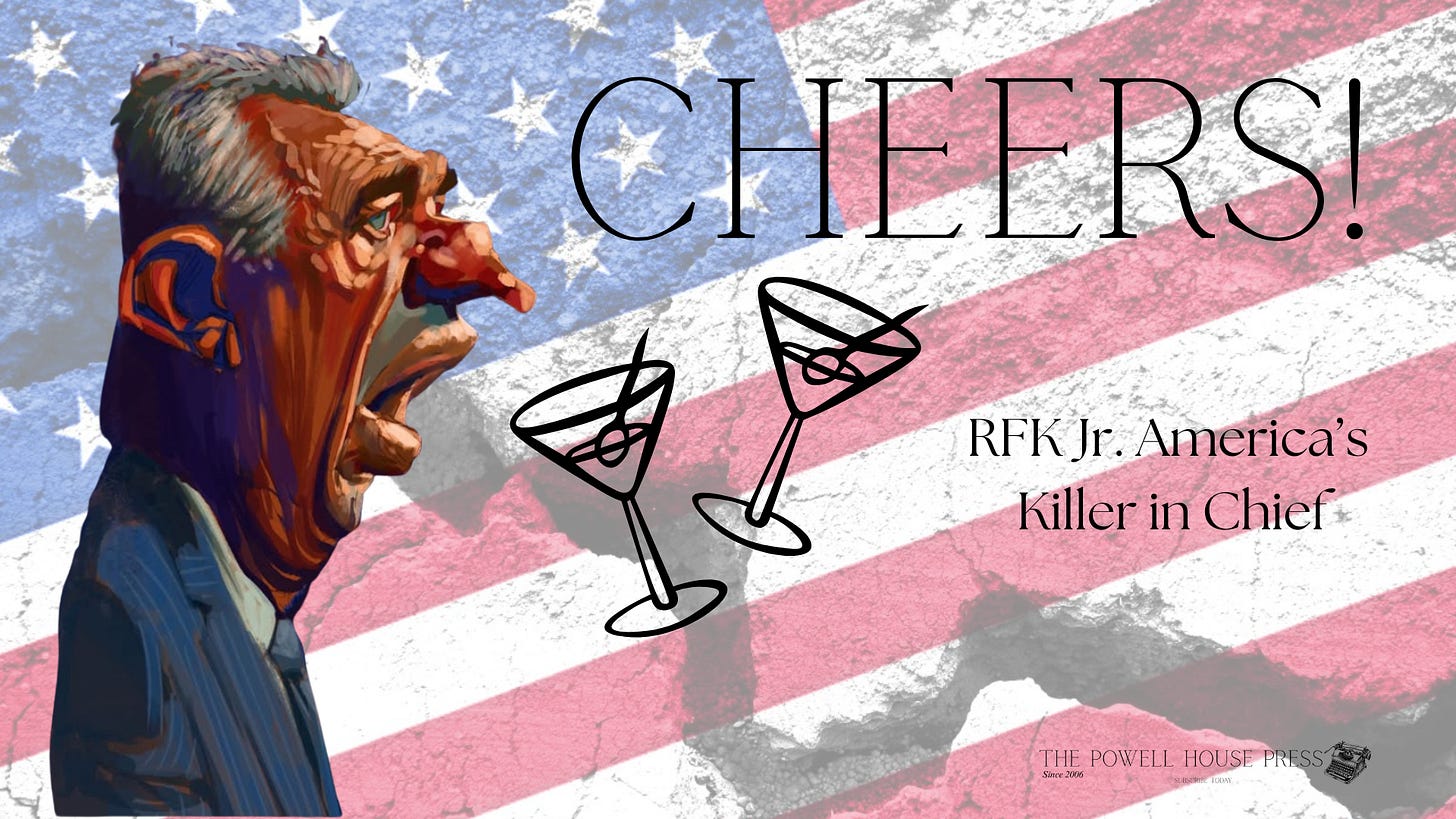

What We Don’t Talk About When We Talk About Making America Healthy Again

Robert F. Kennedy Jr. has a platform, a history, and a responsibility he refuses to honor

Robert F. Kennedy Jr. released his new Dietary Guidelines for Americans on January 7, 2026, and the document is precisely what you would expect from a man who has made a medical career out of law school and a pedigree: a ten-page manifesto that declares war on added sugar while gently suggesting that Americans should “limit” their alcohol consumption—without offering a number, a warning, or an honest reckoning with what this particular poison actually does to human bodies, families, and communities. The previous guidelines specified limits: two drinks per day for men, one for women (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services & U.S. Department of Agriculture, 2020). The new MAHA version eliminates these entirely, offering only vague language about moderation. More than twenty alcohol industry trade associations praised the change, and the U.S. Alcohol Policy Alliance called it “a big win for the alcohol industry” (Washington Examiner, 2026). A movement that claims to be rescuing Amer…